There are quite a few inaccuracies about the various movies in this article, but forgive them. The films weren't so well known and certainly weren't as easily available back in 1979 so it was harder to check these things. They had to rely on memory. It was rare enough for such a long article (7 pages, with pictures) in a major publication. It's a shame that Emeric was relegated, once again, to the role of just the screenwriter and their comments on AMOLAD are hard to believe – Steve

Peerless Powell

By Nigel Andrews and Harlan Kennedy

Film Comment; May-Jun 1979

Ever since Moira Shearer, a Côte d'Azur Anna Karenina, threw herself under the Monte Carlo express at the end of The Red Shoes, English director Michael Powell has had a place in movie folklore and moviegoers' affections. The British cinema's greatest Misfit Romantic – who began his feature film career in the Thirties and is about to add a late chapter to it with the forthcoming Anglo-Russian production Pavlova – has been promoting his visions of wayward emotionalism for forty years. The critical plaudits, late on the heels of popular acclaim, are at last coming full spate. Last November Powell was honored with as full-scale retrospective at London's National Film Theatre. Next year his work will be gathered together and showcased at New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Powell seems at first a bizarre film-maker to have come out of Britain. The traditional view of British movies and British sensibilities – certainly up to the Sixties and possibly beyond – is of a world where the stiff upper lip ruled, where emotions were dispensed with tasteful understatement, and where nostalgia for the Empire hung like a proud but tattered flag above the people's heads.

It was an image of Britain that British movies promoted so consistently in the years during and after the war that it is no wonder it endured so long. It owed its resilience less to truthfulness than to the knock-on effect of cinema fashion. Being a popular, even a necessary, image to cultivate in the war years, it continued after the war more through habit and momentum than through accuracy. British cinema in the Forties and early Fifties – the cinema of In Which We Serve and Way To The Stars and The Dam Busters – comported itself like the nation's Super-ego, keeping a tight rein on dark an potentially "dangerous" passions.

Sometimes, though not too often, the Id raised its voice in protest. It did so chiefly in Powell's films. In collaboration with Hungarian-born screenwriter Emeric Pressburger, he conjured into being such momentously un-British (at the time) screen fantasies as Black Narcissus, Stairway to Heaven, The Red Shoes, and Tales of Hoffman.

"At the time" can be loosely defined as the war-and-after years between 1939 and the middle Fifties. Powell was the resident mischief-maker in the British cinema in those decades – an unruly genius, who though he made his appeasing quota of patriotic films hymning the virtues of British phlegm and courage, also showed the rebellious, delirious side of British character.

At a time when philistine stoicism was the order of the day, Powell was making films about ballet (The Red Shoes), about fairy tale giants and genies (The Thief of Bagdad), about maddened nuns (Black Narcissus), about love and mysticism in the Scottish island (I Know Where I'm Going) and – here surpassing even himself in thematic perversity – about an eccentric in Southern England who goes about pouring glue into girl's hair (A Canterbury Tale).

Powell was also the only British director at the time to work with virtually his own repertory group of actors: names like Conrad Veidt, David Niven, Deborah Kerr, Anton Walbrook, Moira Shearer, Eric Portman and Marius Goring.

It is not surprising – how long could such defiant individualism remain unacknowledged? – that, after a period in the critical wilderness, Powell is now back to being the most feted of Britain's older filmmakers. In addition to the London retrospective, he has just had a book of critical essays published about him [Powell, Pressburger and Others by Ian Christie] and a doctorate awarded to him at a British university. An enterprising American is writing an entire book about the making of The Red Shoes. And to complete the picture Powell, at the ripe age of seventy-three, is preparing a new film: a portrait of the Russian dancer Pavlova, to be made partly in Moscow and Leningrad, partly in Paris, with a final ten days of shooting in London, and to get under way later this year. [Pavlova: A Woman for All Time was finally released in 1983]

It is no coincidence that the worlds of opera and ballet keep recurring in Powell's work. The impulse of his films is almost entirely visual and musical. Powell is one of perhaps one of perhaps only two British directors (Hitchcock being the other) to have fully extricated their movies from the embracing fetters of the English Literary Tradition. In a national cinema cursed by literary bias and shy of visual and aural experiment, Powell in his heyday was like a mad scientist who discovered he had the whole laboratory to himself.

A streak of anarchy runs through nearly all his work. Although he began his feature film career obediently enough with a handful of war films and wartime thrillers – Edge of the World, The Spy in Black, 49th Parallel, One of Our Aircraft is Missing – the expressive breakthrough was not long in coming. The first truly "Powellian" films were the three he made in the late war years: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1942), A Canterbury Tale (1944), and I Know Where I'm Going (1945).

All were scripted by Pressburger, who came to England from Germany after working for ten years with UFA, and there is no doubt that the films owe much of their sardonic outsider's-view of the British character to him. Colonel Blimp is still war-preoccupied in theme but by no stretch of definition could it be called a "war film". Powell's camera has pulled back to take in a huge satiric panorama of British military history. Framed in a "modern" sequence in which the aged, Blimp-like hero (Roger Livesey) has a brush with a group of rebellious young cadets on the eve of World War Two, the film is mostly a flashback account of "Blimp's" life showing how he too was once a young hothead (in the time of the Boer War) and how age and experience slowly mellowed him through sixty years and one earlier world war.

A

recent item in the British Press has revealed that Powell and Pressburger, who seem to have been born to controversy, incurred the wrath of Winston Churchill over this project. Convinced during the shooting of the film that it was to be a vicious lampoon of army manners (the name "Colonel Blimp" was borrowed from a jingoistic cartoon character created by British artist David Low), Churchill issued memo after memo: asking first that the production be terminated, and later – when it wasn't – that the film itself be banned from export. In neither aim did he succeed, but the memos and their replies exist to this day as a cautionary reminder of how close he came.

It is in Colonel Blimp that the first full flush of Powell's genius as a visual stylist – and as a colorist – appears. Designed by Alfred Junge (another refugee from Nazi Germany), the film has a wonderfully rich sense of period, and shows a Hitchcockian flair for using trick effects (especially "glass shots") to give studio settings an extra dimension.

What the film also boasts, more importantly, is the first lengthy elaboration of a motif that was to run right through Powell's work, made with or without Pressburger. Raging quietly at the heart of every Powell film is a battle between emotional contraries – a battle working either towards a wisdom-bringing synthesis or to outright victory or defeat. Powell's emotional contraries are almost all variants on the same archetypal and markedly "British" counterpoint: between inhibition and free-spiritedness. The first category takes under its wing a multitude of Powellian sins – puritanism, moral or artistic conventionality, religious self-denial – while "free-spiritedness" is a living-out of one's own needs and desires in an often self-destructive defiance of social rules.

In Blimp the subtle ebb and flow of the story sweep the central character now to one side of this counterpoint, now to the other. The Establishmentarianism against which "Blimp" declares himself early on to be an enemy is an agent of inhibition; yet Blimp finds an instant kinship with the forms and manners of Prussian gallantry as exemplified by his German friend (Anton Walbrook), whom he first meets in a dueling incident and runs up against regularly during the film.

The film would seem to switch Blimp's character around gradually from freedom to formality, in a sort of two-and-three-quarter-hour moral volte-face. But the present-day framing sequence – the clash with the cadets – is subtler than that. It presents Blimp as an individual, however much inculcated with social orthodoxies, in conflict with a rebellion which, however anti-establishment in spirit, expresses itself in homogeneous "mob" form.

In I Know Where I'm Going – and its post-war companion piece Black Narcissus – the Powell tug-of-war really begins between an elemental, "romantic" individualism and the stubbornly straitlaced heritage of British character and British mores. In the first film Wendy Hiller, an actress whose severe cheekbones and crisp, schoolmistress manner virtually personify British common sense, plays an English girl visiting Scotland to marry a wealthy businessman. Instead she meets, falls in love with, and then tries to flee from a skeptical, roguish Scottish Laird (Roger Livesey).

The central episode, around which the whole film spins, is the scene in which she attempts a perilous crossing by boat from the Laird's estate to the island on which her fiancé lives. The sea will not let her cross. Wind and wave beat her back, in a giant conspiracy of Nature, to the arms of the man whom by her own Nature, she loves.

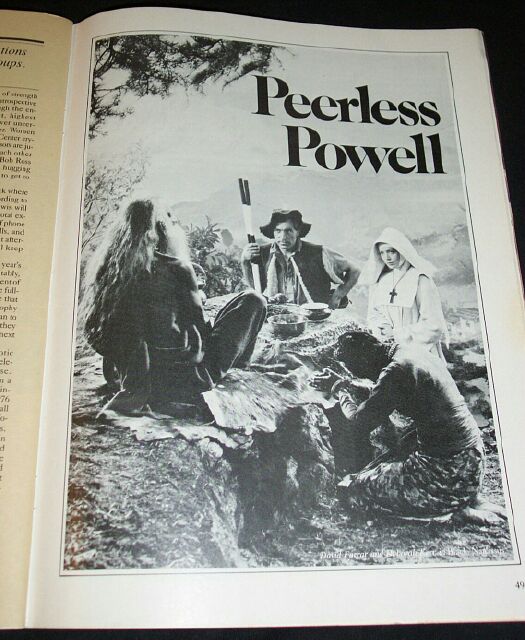

The same kind of battle between Nature and Civilization, between spontaneity and schooled responses – this time those of religion – is waged in Powell and Pressburger's 1947 color film Black Narcissus. The story, based on a Rumer Godden novel, is set in India; but Powell, continuing his role as the British cinema's Imp of the Perverse, decided to make it all in a studio. The results vindicated his decision. A story whose intensity would have been crucially weakened by the injections of travelogue-India is given instead a claustrophobic, hothouse atmosphere perfectly keyed to its tale of British nuns incarcerated in a Himalayan convent and fending off temptations from every source: including Indian exoticism (Sabu as a resplendent Nepalese prince), loss of religious faith (Kathleen Byron as a doubting nun) and Sex (David Farrar as a handsome Britisher given to exciting female hearts by visiting the convent in short trousers).

If there were elements of a simple, al fresco realism in I Know Where I'm Going (made in black and white), Black Narcissus wraps itself in the gaudy cloak if Expressionism. Perched on an almost impossible mountain pinnacle (courtesy of another "glass shot"), the convent and its repressed inhabitants seem to live in a continuous state of vertiginous emotional tremor. The setting becomes a metaphor for the balancing act of religious faith itself. And like the hallucinations of starving men, the nuns' over-excitability at the very notion of sex brings them constantly to the edge of their own emotional precipice.

Aided by Jack Cardiff's photography, Black Narcissus is Powell's triumph as a cinematic painter. The compositions are inexhaustibly eloquent, and the Technicolor golds and browns and yellows shimmer with a Van Gogh-like intensity.

The thematic clash in Powell and Pressburger's stories is often echoed in a clash of opposites in Powell's own style. The Irresistible Force of Powell's natural penchant for fantasy or expressionism meets the Immovable Object of British Realism heritage. And from that confrontation come much of the films' inner tension, and much of their power to fascinate and bewilder.

The three films Powell made at the end of the Forties run a startling gamut of expressive possibilities from the gift-wrapped hyper-kitsch of The Red Shoes to the gritty, monochrome naturalism of The Small Back Room, while the third film A Matter of Life and Death (released in the U.S. as Stairway to Heaven) – set partly on Earth, partly in Heaven, made partly in color, partly in monochrome – offers a sort of stylistic intermediary.

What gives these contrasts of style an inner, secret harmony is Powell's talent for making one extreme always hint at the existence of the other. Though he "buries" expressionism for most of The Small Back Room, one senses it constantly scratching at the coffin lid, and it actually comes out, arms flailing, in one display-piece hallucination sequence. Also, Powell's thematic fascination with the duel between freedom and inhibition runs through all the films, and in A Matter of Life and Death is writ large in a grand showdown between Life and Death.

Life and Death (1946) has worn least well of these three films – chiefly, one suspects, because it began life (like the earlier 49th Parallel) as a government-encouraged propaganda exercise. Relations between Britain and America where deteriorating somewhat after World War Two, and Powell and Pressburger were asked to step in with some cinematic diplomacy. They produced the story of a British airman (David Niven) who is snatched up to Heaven before his time and then allowed back to Earth, "on parole" as it were, where he falls in love with an American service woman (Kim Hunter). Will the heavenly judges have mercy on Niven and allow him to extend his stay on Earth indefinitely?

While it is obviously good for Anglo-American relations that he stays, one is not greatly disposed to care for any other reason. [Did they actually see the film?] The film survives less today for its whimsical, would-be metaphysical storyline than for its visual virtuosity – its attractive alternations of monochrome and color (including the then highly avant-garde "bleeds" from one to another), and its famous "Stairway to Heaven" sequences, which are a beguiling combination of Hollywood-gaudy and the painterly-surreal, as if Busby Berkley had joined forces with Salvador Dali.

The Red Shoes already has a chapter in film history as one of the great classics of refined schmaltz. But it also deserves a footnote as perhaps the only one of their tug-of-war Morality Plays in which Powell and Pressburger do not visibly take sides. We sense P&P rooting for Wendy Hiller's sexual-emotional liberation in I Know Where I'm Going,and for the nuns to climb down from their spiritual pinnacle in Black Narcissus; but in this tale of a demon ballet impressario (Anton Walbrook) and a lovelorn composer (Marius Goring) who vie for theattentions of a young ballerina (Moira Shearer), the sides are more evenly matched. Conjugal bliss or artistic fulfillment? The film keeps us guessing to the end which consummation the heroine will finally select: and then springs the tragic surprise of a suicide conclusion.

There is triteness and sentimentality in the film, but it deserves better than to be relegated to a place in every filmgoer's Museum of Favourite High Camp. It is the first, perhaps the only, film about ballet which embodies the spirit of that art. Indeed if one views the whole movie, and not merely the famous "Red Shoes" sequence, as a ballet, its plot is no dafter or more simple-minded than Swan Lake or Giselle. And its movements are almost as graceful. Powell's Technicolor romanticism revels in the baroque excesses of Covent Garden, and in the photogenic way the Opera House rubs elbows with the fruit and vegetable market. And as the mantle of gothic gloom descends upon the shoulders of Walbrook, the film creates an ersatz tragedy atmosphere far more potent and haunting than (to invoke a recent memory) the soap-opera melodrama of The Turning Point. [1977 ballet film with Shirley MacLaine & Anne Bancroft]

Powell and Pressburger's last film of the Forties was perhaps their best. It is The Small Back Room (1949), a wartime thriller modestly made in black and white.

Blimpishness stalks the corridors of the government-funded waepons research laboratory in which the hero (David Farrar), a disenchanted, cynical, alcohol-prone scientist, works. Slowly and meticulously – for this is a film dominated by shadows, by waiting, by ticking clocks – the hero's character is built up, and so is his antipathy to the Establishment figures who pay his wages and pull his strings. There is also a girl friend (Kathleen Byron) who functions both as domestic relief and as the guardian of his whiskey bottle.

Graham Greene might have drawn the central character – a man constantly hauling himself up by the bootstraps from a despairing nihilism – and there is something Greene-like also about the bureaucratic comedy. In one scene, a top-level board meeting in Whitehall is conducted against the nagging and continuous noise of a road-drill from the street outside.