Submitted by

Michelle Guillot

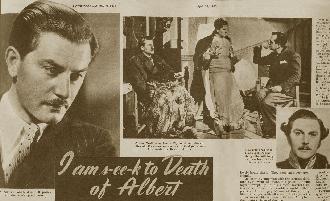

Anton Walbrook Interview

Picturegoer Magazine, March, 1940

I am S-ee-k to Death of Albert

by Sylvia Terry-Smith

When I first met Anton Walbrook he was standing belligerently in the middle of his dressing room, a tall, black-haired, blue-eyed young man, his hands thrust into the pockets of his rather disreputable-looking dressing gown.

"Good afternoon," he said, politely distrustful. "What paper are you from, please - and may I see your card?"

A little nervously I presented my credentials and then looked up to see the rather worried frown chasing itself off Anton Walbrook's brow.

"I will trust you," he decided, and the delightful smile that accompanied this decision dispelled my vague alarm. "You see," he went on to explain, "I have so many young ladies coming up here, trying to see me and pretending to be what they are not - it is so difficult."

Now, put down in cold print, that may sound rather conceited, but I can assure you that when Anton Walbrook made his rather wistful complaint, it was with no over-taxed sense of his own importance.

If ever anyone needed police protection from too-ardent feminine fans, it's this shy, six-foot, handsome young Viennese actor with his enchanting accent and genuine horror of publicity. He really should be labeled public menace number one, as far as the feminine section of his public is concerned.

That meeting was just before September, 1939, when Anton Walbrook was still playing opposite Diana Wynyard and Rex Harrison in Design for Living.

When next I saw him, it was at Denham and he was still playing opposite Diana Wynyard, but this time making the film of that superb play, Gaslight.

It was a gusty, rainy March day, and having missed my train and arrived an hour late, I was just in time for Anton Walbrook to offer me a lift back to town.

I asked him why we heard so little of him here. For really, we know next to nothing of this talented young man who has so endeared himself to us during the comparatively brief time he has been in England.

"You see," he admitted reluctantly, "I can't bear publicity of any kind. I very, very rarely give any interviews." (I knew that, for this was my second attempt to see him!) "I have no publicity agent and I never go anywhere once my work is done. I simply hate being photographed," he went on vehemently. "I make a very bad photograph, you see, that's why there aren't many of me about."

And that wasn't a mere pose - just another publicity gag. Just think for yourself how much you've seen or read of Anton Walbrook in comparison with the other stars who have had much less enthusiastic Press notices.

Have you ever wondered, too, why we have seen so little of Anton Walbrook in films, apart from The Rat and the Queen Victoria films for which he received such outstanding Press notices? I did, too, until he explained to me that afternoon.

"How could I make a film whilst I am acting on the stage?" he asked in surprise. "No, no - I refuse to make a film whilst I am doing something else. I could not possibly do justice to either; I like to concentrate on one thing at a time. I insisted that my next film should not be in costume. I think the public is a little tired of costume films and I - I am s-ee-k to death of Albert! After all, I made two films of him, you understand?" He pulled a face and offered me a cigarette.

Anton Walbrook's father was a world-famous circus clown in the old Vienna.

"When my father was a little boy - five years old - his parents died," said Anton dreamily. "One day a circus with all its tents and bands and animals passed through the town where my father was living and he ran away from home and joined the circus, and that's how he became a famous clown," he explained proudly.

"My father is still alive now, you know; he is in his seventies. Grock was his pupil and he used to come to Austria and see my father. He loved my father and my father loved him and would go to Italy and stay with Grock in his lovely house there. They were such great friends."

And as this young man with the earnest, dark-blue eyes went on without a pause, I found myself swept up in his almost reverent enthusiasm, into another world, a world without politics, the old, gay Vienna of thirty, forty, fifty years ago, with all society flocking to the circus to see this supreme artiste - "Adolphe", the greatest clown of the age.

"My father was wonderful; he was so great, the best artiste there ever was!" Everybody would come to see my father," went on Anton with a faraway haze in his eyes. "All the famous producers and actors would watch him.

"Always they asked him to go on the stage. Max Reinhardt asked him why he wouldn't go, and my father said why should he bother with having to learn long speeches? No, he loved what he was doing in the circus. It is funny, what I am going to tell you sounds like romance, a novel, but it is all true," he broke off to explain, then went on eagerly in answer to a query.

"No, I never wanted to follow my father's footsteps - that is wrong. I never wanted to be a circus artiste at all and I could never understand why I didn't. Always for me it was the stage. I wanted to be an actor and I used to wonder why it was, for surely I should have wanted to be in the circus like my father?

"Still, I joined a repertory company and toured the Continent. I was very lucky to be in Germany then," he interpolated. "Here in England it is very hard for beginners, but in Germany - the old Germany - young actors had every opportunity.

"They would have a two or three year's contract and the producer would take an interest in them and devote his time to building them up into big stars. Here it is much, much harder for young people.

"However, I went on the stage and one day a Mr. Paul Wohlbruck - same name as I had - I was not always Walbrook, you know - wrote and asked me if I was any relation to the famous clown. And then he told me what I never knew before. He was a great, great uncle of mine and had traced my "pedigree" and found that for the past two hundred and fifty years my family had all been actors - with one single exception -- that was my father who became a circus artiste!

"And that, of course, explained what I could never understand before. Why I had to go on the stage - you see, I just had to be an actor, I couldn't help it."

And so young Anton Walbrook (or Adolph Wohlbruck, as he was then -"Not a very popular name now," he grimaced), went on to tour the Continent, playing every conceivable kind of part, singing, dancing, straight plays, drama, operettas, Shakespeare. "Oh, how I love Shakespeare," he sighed. "But here in England it is impossible for me to act it."

(Oddly enough, he was unconsciously echoing a heart-cry from another Continental actor. Conrad Veidt expressed the same wistful complaint to me in almost the same words!)

"It is the same with Bernard Shaw," went on Anton. "Many, many times I have played in Shakespeare and Shaw on the Continent, but in English it is too difficult.

"One of my very first stage parts on the Continent," he went on, "was the leading man in that play - it has been made into a film with Robert Taylor and Greta Garbo, now what is it called? "La Dame aux Camelias," en francais en anglais? er - yes, "Camille." And from that I went on to play everything under the sun."

Then he echoed yet another Veidt grievance -- the difficulty of finding suitable plays in England.

"You see, not being an Englishman, there are so few suitable parts for me in English plays and film scenarios," he grieved.

And one of Anton Walbrook's greatest desires since he changed his name when he came to England, is to become more English than the English. "Ever since I came here I've tried so hard to lose my accent, but I've still got it, you see!" he sighed.

Fortunately for us he has not managed to achieve this yet - because he is far too charming as he is. Now he is waiting to take out naturalization papers and his heart seems as passionately English as any Englishman's. There is no doubt about it. Anton Walbrook has taken the English to his heart as enthusiastically as we have adopted him.

This difficulty in finding suitable plays, however, led me to ask if he ever wrote anything for himself.

"Oh, no," he laughed. "I try, yes, but I can't write plays. For one thing I have no time. But I wrote my first novel when I was fourteen. Oh, it was very romantic, very tragic - at least ten people died on every page!" he chuckled in recollection. Then I asked him how his film career started -- he has made films in French, German and English - and he told me how it took him two years of trying before he entered film work.

"You see," he explained, with a shy side-glance at me, " the trouble was I make such a bad photograph. They kept on trying to photograph me but it was no use. My face was not made to be photographed. Then one day they asked me to grow a moustache, for they wanted me to play Johann Strauss, and I protested, and for a long time would not have one.

"So they stuck one on me and behold, I photographed all right then; that moustache seemed to alter my whole face and made all the difference in my pictures. So afterwards I grew a moustache. At first I thought the ladies would not like it, but they did, and ever since I have always had one, my very own now," he grinned and caressed it affectionately.

You know, that's not just a moustache, Mr. Walbrook. You have joined the very exclusive little band of men whose badge is an upper lip bearing a distinct asset -- almost an unfair advantage.

"You might say I owed everything to my moustache, everything but my talent," he laughed. Anton, you see, is justly proud if his ancestry.

I asked him what career he would have chosen had acting been barred to him. "There's nothing," he assured me decisively. "Nothing but acting or - die. And what is my ambition? Just to go on acting, of course. Not to make a lot of money. What's the good of it these days? And anyhow, you can't save money today.

"No, there's nothing I'd rather do than act, unless, yes, unless I'd been born a millionaire. The I would travel all round the world and never, never look at a newspaper."

"One thing I am very grateful for," he admitted earnestly. "and that is for the privilege of living in England. It is a wonderful country and I cannot tell you how thankful I am to be here now," he finished with a swift smile of gratitude which embraced not only myself but the whole of England.

"You know, just before we started making this film we were touring the provinces with Design for Living and I was in what you call them - digs, you know - all over England, especially the Midlands and northern counties. Any everybody was so nice to me wherever I went. The landladies were so kind," brooded Anton. "But everywhere it was the same; the simple people make you feel at home at once, but not the highbrows. I don't like them." He wrinkled his nose and screwed up his eyes in disgust. Then as we slowed down at a crossing he turned to me seriously.

"You know," he started, "it is so nice to be working hard again. When war broke out and the London run had finished, I was grateful for the tour - it helped keep my mind off things. And whilst I was in the Midlands - and oh, how drab and gray and miserable are the manufacturing towns," he sighed, "-I was sent the scenario for Gaslight. I haven't seen or read the play, but there on the dull December day, in that depressing town, I sat and read the story, enthralled and at once I felt I must accept.

"Diana Wynyard was astonished when I told her," he laughed, 'but it is such a marvelous play; the man is so incredibly wicked. Shakespeare never created anyone half so terrible.

"So I felt it was a great opportunity for an actor and such a different character from my recent ones. On the Continent I got into a lot of trouble because I would insist on playing the hero and then the villain; one day being a gentleman, the next a low thief," laughed Anton reminiscently.

"And here it is the same," he went on wistfully. "Though I'm rather wondering how the public will take this particular film. The thinking public who understand it will enjoy it, I know," he pondered thoughtfully. "But those who accept film superficially - well, I don't think perhaps they will enjoy it so much," he shrugged.

Actually, the emotional stress of Gaslight is such that even publicity folk are barred from the floor whilst shooting is in progress. The acute mental strain takes a lot out of everyone concerned with the production.

"I had to be so careful in choosing this film, you know?" want on Anton, eyes on the road now. "You see, it's so important that when an actor has been away from films for a little while, his next film should be up to the standard of the previous ones. So although I had a lot of films offered me, I did not decide on any til I found this - such an outstanding play. And it's going to be a simply a marvelous film," he added, his voice brimming over with confidence and a sort of "I-dare-you-to-contradict-me" note.

"And afterwards?" he echoed. "I think I shall make two or three more films yet before I go back into a play. Six evenings and two matinees a week for months on end are a strain on any actor," smiled Anton. "Although all actors should spend a certain amount of time on the stage and I myself much prefer it," he said emphatically.

Back to index