The Films of Michael Powell

A Romantic Sensibility

David Thomson

An appreciation of film's gentleman poet, whose work has ranged from the

fanciful Red Shoes and Thief of Bagdad to the daring Peeping Tom.

Moira Shearer in The Red Shoes, Michael Powell's

brilliant evocation of the backstage world of ballet. |

In his seventy-fifth year, Michael Powell strode through the New England winter in a deerstalker and a tweed cape. The colder the day, the fiercer the cherry glow of his face. In February, with the ground hard as iron and the wind rushing in from Labrador, he was out and about directing students from Dartmouth College in his latest production, regretting that there was so little snow.

An unaccountable mock Egyptian building on the campus had been appropriated as the entrance to the tombs of Atuan. A wizard had come there after a great journey, while within the tombs a child priestess danced her life away in ritual ceremonies. The wizard had one half of a broken ring, the child the other. When the two halves joined, the air filled with music, the oppressive tomb cracked, and the leading characters would escape. It is an incident from a series of fantasy novels, The Earthsea Trilogy, by Ursula Le Guin. But for Michael Powell it was all real, resonant and inspiring. Why should he not believe in wizards, when he had seen such transformations in his own life?

The year before he had spent in England, like so many years before, traveling between his cottage in Gloucestershire and the Savile Club in London. He had several projects in mind, fantastic films that might be made if the world was more sensible, but he spent a lot of his time on long country walks, reading, and cooking. If he didn't think of himself as retired, he was in that serene, downhill stage of his walk in which momentum eased tiredness with the certainty of being home before dark. He had not made a feature film in over ten years, and that last work, Age of Consent (1969), had been shot in Australia and was never shown very widely. In the years since, he had made one short film for children and he had gone back to the Scottish island of Foula for BBC-TV to shoot an epilogue to The Edge of the World, a picture he made in 1937.

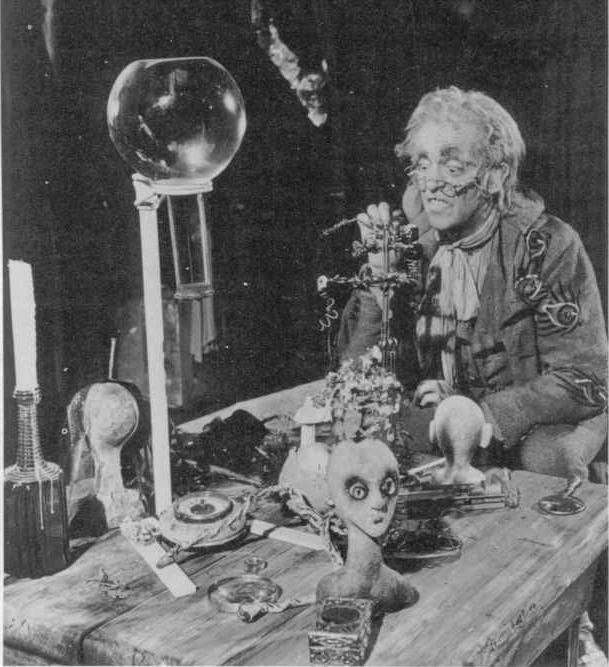

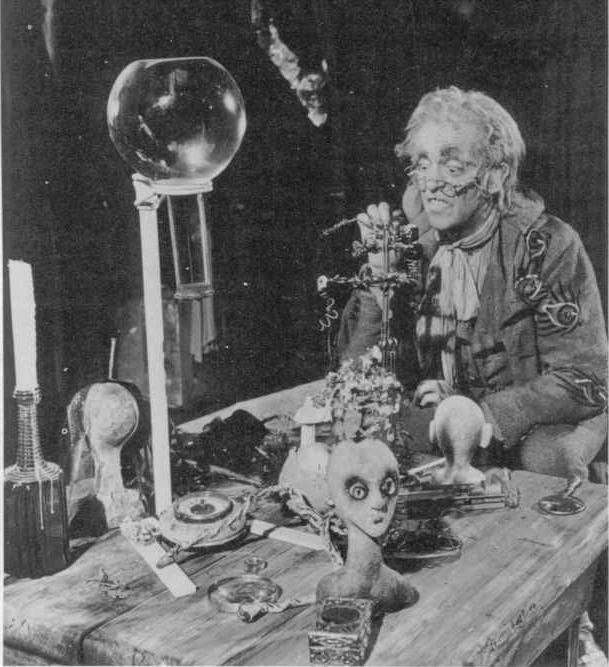

The Tales of Hoffmann, Powell and collaborator Emeric Pressburger's

richly textured mélange of opera and dance.

|

But late in 1979, Peeping Tom (1960) was given its first proper American release. So savaged by the London critics, it had had a miserable showing in America in a cut version. Now, Corinth, encouraged by Martin Scorsese, struck new, complete prints and made the still-haunting Tom one of the events of the 1979 New York Film Festival. Two years earlier, it had been Scorsese who appeared at Telluride to acclaim Powell, owning up to the huge imaginative influence of the nearly forgotten director.

Peeping Tom disturbed and excited as much as ever in 1979. Some critics flinched from its stealth, humor, and passion. Elliott Stein wrote a panegyric in Film Comment, and Paul Schrader called it "a cinéaste's secret treasure. Every pale, overweight, lonely film student who has spent hours in dark rooms watching old movies cannot help but identify with this film." Around the time of the New York festival, arrangements were made for Powell to be artist in residence at Dartmouth in the winter, and to teach a course in film production while he was there. During that tenure, he was besieged with invitations and phone calls concerning Peeping Tom. What did he think about it being picketed by feminist groups? Would he attend showings? Would he explain its dark significance?

Michael Powell took everything in his brisk stride. He is no explainer: Wizards prefer to amaze audiences and let such as Susan Sontag analyze Peeping Tom. It is the tradition of Georges Méliès, Fritz Lang, Rex Ingram, Alfred Hitchcock, and Star Wars, companions in magic that Powell honors. He had no need to explain, so much else was happening. The Museum of Modern Art had announced a retrospective for November 1980, drawing upon prints carefully assembled and restored by the British National Film Archive. With that series, anyone would be able to follow the sequence of films that had captivated Scorsese, Lucas, and Coppola: The Thief of Bagdad (1940), 49th Parallel (1941), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Canterbury Tale (1944), I Know Where I'm Going (1945), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), The Red Shoes (1948), The Small Back Room (1949), Gone to Earth (1950), The Elusive Pimpernel (1950), The Tales of Hoffmann (1951).

Those films mark a decade of astonishing achievement, violently and triumphantly set against the grains of war, austerity, and rationing in Britain, sublimely indifferent to that respectable national illness known as "documentary." Powell was not alone in the late forties: David Lean, Carol Reed, Alexander Mackendrick, and Robert Hamer were doing fine work, too. But no one else made the cinema such an Ali Baba's cave in such gloomy, cautious years. The forties are Powell's heyday exactly because it was the least likely decade for his wild imagination. In the middle of the war, with Colonel Blimp, he had made a two-and-a-half-hour picture about the bumbling of the British military and a profound Anglo-German friendship, despite the resourceful opposition of Winston Churchill. And in the most anxious period of the cold war, he had filled the screen with color, dance and the radiant message of art above everything that makes The Red Shoes a film no one ever forgets.

At Dartmouth, Powell filmed in the afternoon and evening. Soon after midday, he appeared in his office ready to go. But the mornings were put aside for the autobiography he started in New Hampshire. That was a task he had attempted several times before, but now at last he had found a form, and perhaps a drive, that made the book work. Coming back to life, working with the young, may have convinced him how extraordinary his career had been.

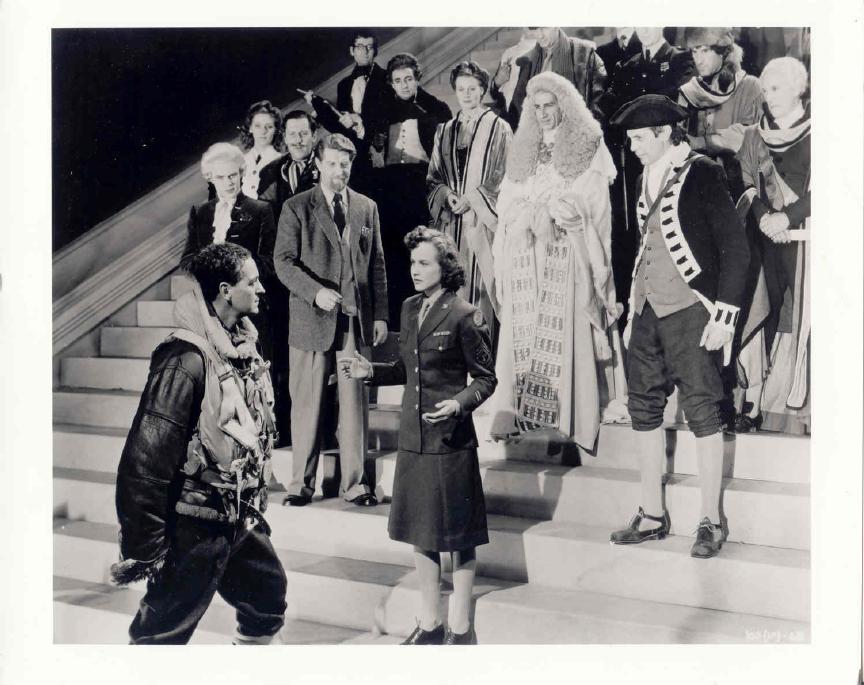

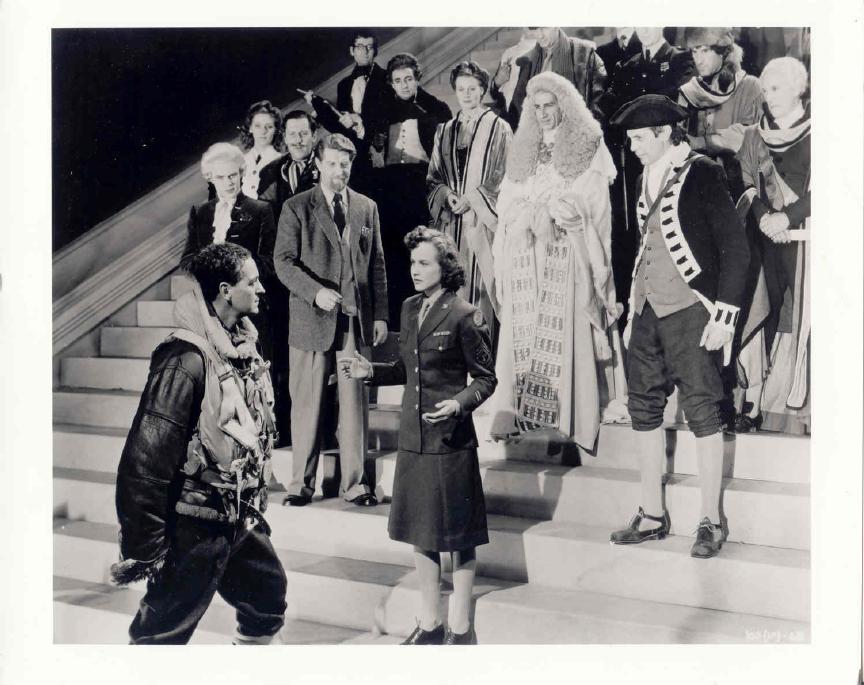

Powell's personal favorite: A Matter of Life and Death, with

David Niven as a pilot trying to cheat death. |

He was born in Canterbury in 1905. He went to school there first, and then to Dulwich, before, at the age of seventeen, he started work in a bank. Already he was determined to be in pictures, but he could find no way in. It was a problem that only magic, fate, or luck could resolve. Powell's father was a gambler, and one day he happened to win a hotel at Cap Ferrat near Monte Carlo. The holiday home for the young bank clerk was also a gathering place for artists, exiles and celebrities living on the Riviera: people from the Diaghilev ballet, members of the Scott Fitzgerald set, and associates of Rex Ingram, who was working at the Victorine studio in Nice.

Ingram was a famous refugee from Hollywood. He had established his own kingdom in France, with his wife and actress Alice Terry, when Metro denied him the director's job on Ben-Hur. It was one of those confrontations between the new studio system and producers and a kind of vainglorious, strutting director who had helped establish the business with The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and Scaramouche. Ingram impressed Powell as someone who might give him a chance, and as a rogue genius who had elected to work outside the system. He was also a director in love with fantasy and mysticism. Powell was his assistant on The Magician (1926), based on the exploits of Aleister Crowley, and an unrestrained adventure in exotic atmosphere. It must have been an extraordinary beginning for the young pilgrim from Canterbury, mixing with the Ingram company and seeing the full imaginative force of movies: "Ingram had an epic style. He also had the grand manner," Powell reflected fifty years later. "These are things you don't forget if you see them when you're young."

Harry Lachman was a painter working for Ingram, and when Lachman went to Britain to pursue his own career as a director, Powell went with him. He got odd jobs: still photographer on Hitchcock's Champagne (1928), and later some uncredited script work on Blackmail. He directed his own first picture in 1931: Two Crowded Hours - a forty-three-minute quota quickie, made for about three thousand pounds.

Powell worked hard all through the thirties on poor material, learning craft and handling every genre that came his way. Still, by 1937 none of his films had been longer than eighty minutes or attracted much attention. He got his best reviews for The Edge of the World, a project that began as an attempt to deal with depopulation and hardship in the Scottish islands, but which became a celebration of mystical extremism. The very title stands for Powell's belief in people who have gone beyond the rational and the everyday, for whom the circumstances of actuality are always lit by imagination.

This was the very opposite of John Grierson's approach, and it was hardly appealing in a Britain advancing on war. Still, The Edge of the World won Powell a contract with Alexander Korda, and that in turn led to Powell meeting the man who would be his closest friend and collaborator, Emeric Pressburger. Pressburger was a Hungarian who had been working as a scriptwriter on the continent. He came to England in 1938, met Powell and wrote The Spy in Black for him, about an ingenious German U-boat captain (Conrad Veidt) intent on sabotaging the British Fleet at Scarpa Flow.

Their partnership developed into an independent company, the Archers, with a target logo and an arrow hurtling into the bull, that lasted until 1956 and is a friendship that has never been broken. They coproduced their films, with Powell directing and Pressburger responsible for the writing. In hindsight, it is possible to see that Powell needed a collaborator, and was blessed in finding Pressburger. Not many of the films made without Pressburger's assistance have been as assured, as well constructed, or as commercial.

Powell's commitment to extremism leaves him oddly unworldly and innocent. He has a soaring confidence in art, a blithe taking for granted of detailed planning. At Dartmouth, and I suspect everywhere else, he could be both inspiring and disarming with a shrug that said "Anything is possible," and threatened to ignore all the mundane matters of budget and schedule. Time and again, his pictures glorify the exhilaration of creative work, and the cold, blazing zeal that separates the artist from reality. Lermontov (Anton Walbrook) in The Red Shoes and the young man in Peeping Tom are extreme portraits of something that Powell himself exemplifies, and which is as unnerving as it is reckless in the picture business - that the art is all-important.

As the war began, so Powell proved himself. And it was an absolutely characteristic streak of perverse originality that in the early forties so many of his films were respectful of German decisiveness, and made in ways that showed the influence of UFA in the twenties. The Thief of Bagdad is a fantasy, wittier and prettier than anything made by Fritz Lang, but every bit as dedicated to a realm of make-believe created on sets. A onetime colleague of Lang's, Alfred Junge, joined the Archers as art director. In 49th Parallel a U-boat crew struggles to survive in Canada: It is an epic allegory about the issues of the war, with Leslie Howard as the spirit of humanism, living in a tent with a Picasso, Eric Portman as a ruthless Nazi officer, and Raymond Massey as the laconic, homespun Canadian who captures the Nazi on the brink of escape to America.

The next year, Powell and Pressburger took the same story and played it in reverse: One of Our Aircraft is Missing is about a British bomber crew in hiding in German-occupied Holland. That starred Eric Portman again, as did A Canterbury Tale. Powell has always liked cold, abrasive, supercilious men, so restrained that the stiff upper lip begins to tremble with hysterical feeling. It is the code of the gentleman allied to the fervor of romanticism, and if it has always disconcerted some viewers, it is the essence of Powell. In person, he is amiable, but cool and teasing; and on celluloid, he acknowledges emotion obliquely or in the artificial frenzy of color, music, dance, and stylization. His best work is torn between the duties of being a gentleman on the one hand and a poet or magician on the other. It may bespeak personal unhappiness - such as Peeping Tom explores with startling candor - yet Powell's sprightly vitality and military uprightness only remind you of the gentlemanly code that prefers not to discuss more intimate things.

Another example of that manner is Roger Livesey, who played Clive Candy, the hero of Colonel Blimp, the Scottish laird in I Know Where I'm Going, and the brain sugeon in A Matter of Life and Death. These are indescribable films, made with what Powell now apologizes for as "shameful ease." In I Know Where I'm Going, Wendy Hiller is on the point of marrying a successful businessman. But on the way to her wedding - on a Scottish isle, again - she discovers her true calling (feeling, romance, imagination) and frees the laird of Kiloran (Livesey) from a curse that hangs over him. It is a movie about the abiding enchantment of superstition and legend, shot in the Hebrides and in a studio tank, filled with a love of Scotland and of surrealism. Premanently enigmatic, cruel, and fey, it represents the innate spirit of faerie in Michael Powell that keeps him from a sure grasp of reality.

A Matter of Life and Death is about a bomber pilot (David Niven) who falls in love with a radio operator (Kim Hunter) in the moments before his "death." In heaven he claims a reprieve on the grounds of that last-minute love, and so a bizarre trial is arranged in a bureaucratic, monochrome heaven, while on earth (a technicolor paradise) Niven prepares for a brain operation that may cure his hallucinations. It is Powell's favourite film, still, one in which he seems to have played like a child. There is hardly another example of a commercial feature feeling so much a work of whim, sport, and impulse, or of those passing fancies turning into dreamlike effects. Alfred Junge built a stairway to heaven; there are ping-pong games that freeze with time; and there is the lovely and mysterious resemblance between the trial in heaven and the operation Niven faces that makes everything in the movie a reflection of something else. Its mood is cheerful enough, but A Matter of Life and Death is the work of a sunny Buñuel.

After the war, Powell and Pressburger wanted rapture, not austerity and ration books. They re-created the Himalayas in a studio and made Black Narcissus, about a convent that is overshadowed by David Farrar as an intensely sexual rogue male. Deborah Kerr was the mother superior; Kathleen Byron was a nun on fire with repressed libido; and Jean Simmons was a native girl such as Gaugin painted. Steeped in color now, Powell had Jack Cardiff as his cameraman. They enjoyed the glory days of Technicolor, before the process opted for high fidelity, cool accuracy, and anonymity, when every color was exaggerated and it was possible to paint with light.

The peaks of that process, I'd say, are Duel in the Sun and The Red Shoes. The latter was a Hans Christian Andersen story that Pressburger had scripted before the war, and that Korda had wanted to make with Merle Oberon. Some ten years later, the Archers rescued it. Powell found Moira Shearer and reunited Robert Helpmann and Leonide Massine for the choreography, Hein Heckroth for the sets. He also cast Anton Walbrook as the im

Back to index