ROGER LIVESEY

The Livesey Family in the theatre 1840 - 1975

Jill Watt

Roger Livesey meant an incalculable amount in my life, although I never met him.

Five weeks before he died I wrote to him, unaware that he had ever planned or researched a book about his family, suggesting one and offering to help in the work. He was already ill, and could not reply.

This is a project description for THE POMPIN' FOLK - a book very specially for him.

The story of the Livesey family is as it was told to me by Eileen Livesey, widow of Jack, the last of the generation who knew and loved them all.

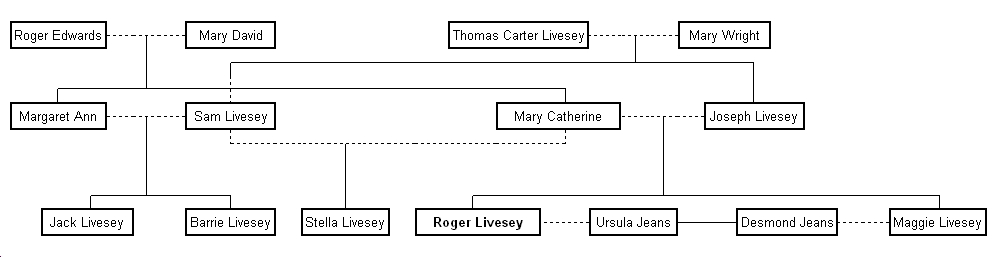

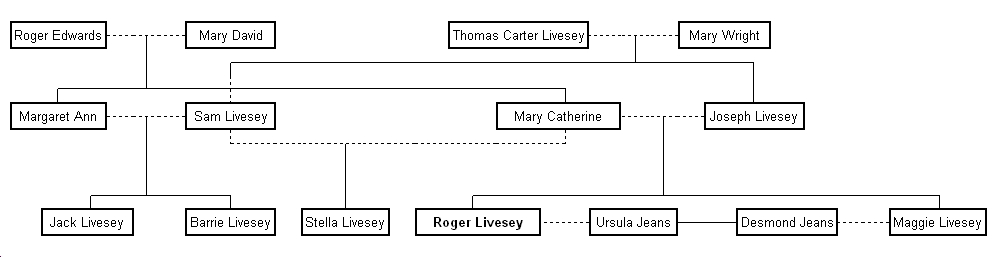

In 1840, for sheer love of the theatre, Thomas Carter Livesey, till then a railway engineer, threw up his job and bought "the largest portable theatre in Europe". With his wife Mary, and in due course their six children, he set out to tour the mining towns of South Yorkshire.

The family travelled in caravans behind a cavalcade of horse-drawn wagons which carried the 1,000-seat red wooden Paragon Theatre (Pit, Gallery, Coke Fires in Winter, All Disorderly Persons Expelled and No Money Returned) to people who had never encountered theatre in their lives before. Mary, Thomas's indomitable support in all adventures, was his leading actress, the six children formed the orchestra under his conductorship for the overture, and then ran backstage and appeared in the performance.

The Liveseys played glorious melodramas of good and evil, with patriotic finales, usually featuring their staunch friends the local Fire Brigade; and boisterous and cryptic farces, often hastily noted down by a member of the family in a rival theatre a few weeks before. But also the whole canon of Shakespeare, and dramatisations of all the books of Dickens. They might sometimes be imprisoned all night in the cattle pen of some suspicious new community, as probably unfit to mix with the locals; too little money and too much weather might add daily to the challenge of putting on the best shows they could devise. But they set imagination alight in little town after town, playing nightly to packed houses of brand-new theatregoers, who never forgot the magic of "the pompin' folk".

Their ambition became the building of a permanent theatre of their own, and Thomas and Mary settled on Mexborough, their favourite touring date, as its site. Before the project could be begun, however, Thomas died, at only 52. Mary was left with six children and a company to sustain. But, undaunted, she determined to complete his work, and Mexborough rallied to her. No one forgot that, during a particularly harsh strike at the mine, Mary had shared her own food with starving miners from the window of her caravan, and handed out free theatre tickets, too, not to neglect their hungry souls. All the principal businessmen of the town contributed to secure her mortgage, and Mary built the Prince of Wales Theatre - no modest approximation of a building, but a first-class modern theatre of large capacity, fully equipped with nothing but the best. It opened to full houses and with much pageantry (involving, as usual, her loyal friends the Fire Brigade) and the Livesey children moved at last into a permanent home of their own; a solid terrace house nearby.

All the family were already seasoned actors, notable among them two of the brothers, Sam and Carter. Sam was a strong personality, an heroic actor of splendid physique and presence, who also made his mark as a local sportsman. Carter, thinner and darker, made a saturnine villain and an effective broad comedian. The brothers and sisters grew up playing everything under the sun in their own theatre, and though they guested with other companies whose members also played at the Prince of Wales, their work naturally revolved around Mexborough. One performance there featured no less than 14 members of the Livesey family. Mary Livesey made her farewell to the theatre as Queen Gertrude to Sam's Hamlet, just before one Christmas, happy that the next generation had already taken up the torch.

Sam and Carter's particular hit was their joint touring production of The Village Blacksmith, a vintage melodrama culminating in a famous wrestling match. In this, for more than a decade, audiences of every kind nightly joined, from the Theatre Royal Bristol to tents on village greens, flinging themselves with alarming enthusiasm into the final triumph of Sam, a grand hero, over Carter as the mustachioed villain. It was a famous show.

By now Sam had married the beautiful young actress Maggie Edwards, and Carter the striking and formidable Cassie le Grand. In 1906 Sam and Maggie's son Roger was born, in Barry, South Wales, where Maggie's mother lived. She looked after her daughter during the confinement and cared for the baby when Maggie went back on tour - an arrangement which worked so well that it was adopted for later children of the family; Roger's sister Peggy, and Carter and Cassie's two sons, Jack and Barrie. The children, growing up so closely together, all went on stage together too, as soon as they could walk if not before.

Then Maggie died, while her children were still small; and within a short time Carter, too, had died. Sam and Cassie, both widowed, were drawn together and fell in love, but the relationship at that time involved a 'forbidden degree' - it was illegal for a man to marry his dead brother's wife. They decided to take a momentous step; marry they did, and undertook the theatrical equivalent, in those days, of an inter-planetary trip. Taking all the four children as their own, they set out to become "London actors". A daughter of their own, Stella, was added to the family, and all five were subsequently known to the world as brothers and sisters.

A fellow actress shared the care of the children when Sam and Cassie were touring, and they spent a happy and united childhood in North London, cycling together round the district and - of course - appearing frequently on stage. Roger had first played in the theatre when he was five, and Sam and Cassie saw to it that he and the others went to the Italia Conti School; where his early success as Cubby the Lion Cub in Where the Rainbow Ends was perpetuated on silent film, making him wonder if perhaps he should specialise as an animal actor.

Roger had no desire, in fact, to be an actor. He wanted to be some sort of a builder or engineer - reverting, interestingly, to the earlier strand of his grandfather Thomas's career. Nor did his "brother" Jack set out to tread the boards - he yearned to be a professional cricketer. But Sam, who had made an immediate reputation in London as a fine character actor, and the loved but formidable Cassie, who acted less these days but channelled all her determination into fostering the children's careers, dictated otherwise. Sam, no doubt with memories of being imprisoned in the cattle pen, insisted that no son of his should adopt a profession in which one player entered a cricket ground by a door marked 'Players' while others were designated 'Gentlemen'. Roger, though he often tried to escape auditions by taking refuge with Jack and his young wife Eileen in their first home, never succeeded in eluding Cassie's eagle eye for long enough to avoid frequent stage engagements, enthusiastically though he tinkered with engines on Eileen's kitchen table in retreat.

He made his first West End appearance as the office boy in Loyalties in 1917, and his future was laid out for him; though he still had odd pictures of how his career might develop, and at one time, perhaps with his father's physical feats in mind, thought of becoming an acrobatic actor - till he elected to do a dazzling handstand at a not entirely appropriate audition, with disappointing results. It was not until his tour with the Florence Glossop-Harris company in 1926 that he became fully reconciled to his role in life, for the reasons that mattered to him most. He suddenly realised, he said in a broadcast, what one's performance in the theatre could mean to people...

The Liveseys were busy not only on stage, but in the early cinema - a suitable equivalent to the popular touring theatre of Thomas and Mary's era - where 'quota quickies' insatiably demanded highly experienced one-take professional actors, dovetailing the hastily-produced films with their West End stage performances. By the early 30s Sam and his sons had made more than fifty films, and the whole family, including Cassie, appeared as a theatrical family in Variety, a story linking a collection of vintage music hall acts, with more than an echo of their own history. Then Roger appeared with Sam in the memorable production of Richard of Bordeaux which established John Gielgud as a star, and soon afterwards was engaged by Harcourt Williams for his innovative first season as Director at Lilian Baylis's Old Vic. At the Old Vic Roger had personal successes in Shakespeare, and in The Admirable Bashville - which featured him in a boxing match reminiscent of Sam's triumph in The Village Blacksmith. He was remembered for sometimes sleeping through calls to rehearsal - but most of all, young though he was, "as my encourager", said Harcourt Williams. It was an effect he was to have on other people all his life.

The Old Vic season brought about Roger's first meeting with Ursula Jeans, a charming young actress, recently widowed, of Anglo-Indian upbringing, who had begun to make her name in the West End the year before. Her brother Desmond, a boxer as well as an actor, married Roger's sister Peggy, now becoming established in the theatre herself. When Roger went on tour with The Country Wife to New York in 1932, Ursula heard that another actress was interested in him - and set out to follow him at once. They were married within weeks, beginning an ideally happy partnership. "I am going to be your sister-in-law!" Ursula formally announced to Peggy. "But you already are!" replied Peggy, her brother's wife.

Returning to England, the young couple quickly made their mark in films. Ursula was particularly successful in Noel Coward's Cavalcade, in which she sang 'Twentieth Century Blues'. Roger was signed up by Korda, appearing within the same year as romantic lead in The Drum and - at the age of 28 - as the ancient beggar Saul, the painter's model, in Korda's magnificent film Rembrandt, in which Sam, Jack and Barrie also appeared. Roger's performance was hailed at the premiere as a personal success - but he had missed the occasion, hurrying to Sam's deathbed. During Sam's last film, he had been told that an operation was inevitable and might kill him. He had asked the director to re-schedule his scenes, and postponed surgery until his performance was complete - true to his principles, a trouper to the end.

At the outbreak of World War II Roger and Ursula were established leading actors, part of the dazzling set who gathered around Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. They kept a flat in town, but their personal life was centred on the country, in the tiny cottage which had been the only thing they could see out of their caravan window when they got lost in a fog on holiday - Plough Cottage, postally addressed 'Under-the-Heavens', a little place like nowhere else on earth. They lent it to the Oliviers as a honeymoon retreat during the filming of Lady Hamilton, and built a summerhouse in the garden for Olivier to occupy later, whenever he was filming at Denham nearby.

Roger was doing his war service in an aircraft factory when Michael. Powell - who was struck by him when he auditioned for The Phantom Light, but was unable to "sell" him to the producer, Michael Balcon, who disliked Roger's distinctive husky voice - had him released to play the title role in his masterpiece The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Powell (a great director who tended to make his marvellous films by instinct and analyse them, less marvellously, by intellect) was still heard even long afterwards, to remark that his original intention to have Olivier in the part "would have sharpened the satire". But Roger added a whole extra dimension to the film, and Colonel Blimp, most movingly, became a British Don Quixote; outdated, sometimes laughable, but the noblest, most touching and enduring character in the film - an English epitome. Roger engineered a telling small part for Ursula in the film - without mentioning that she was his wife - and her brother Desmond, Peggy's husband, also appeared as a barman.

Blimp, though Churchill tried so hard to ban in wartime its humane and provocative portrayal of a lifelong friendship between a British and a German officer, was warmly praised on its release; but it has taken two more generations to give it its full status as a major classic of the cinema. Powell followed it with another offer to Roger which he and Emeric Pressburger - in an uncharacteristic blind moment - also saw as an English epitome; the role of the glue-throwing magistrate in A Canterbury Tale. Roger, who never intellectualised, sensed this was off-key. The Powell role he did want - one which (again oddly) was first destined for James Mason, a very different kettle of fish - was a British epitome, if not an English one; the impoverished Highland laird in I Know Where I'm Going. This Archers end-of-war production, apparently a simple love story, at another level asked questions about the values for which peace had been gained. Roger played the man to whom ideals and heritage matter more than money and apparent success, who wins the heart of an ambitious and materialistic girl.

The last of his major roles for The Archers, in A Matter of Life and Death, the film chosen for the first Royal Film Performance, was similarly meaningful; that of the benevolent surgeon who becomes an advocate before the Heavenly Court for the soul of a pilot who claims a fresh lease on life, having fallen in love during the time in which he was destined to die.

In each of these major roles, played in his early 40s, something of a unique quality in Roger's personality was especially captured; a quality which meant something lasting to everyone who encountered it. And on those very films Wendy Hiller and Kim Hunter remember with special gratitude how he made a point of teaching each of them how to weather the experience, notoriously destructive to a young player, of working with Michael Powell - and, still more importantly, how to reach through that to make a friend of Powell the person, a good friend of his own.

Roger's performance in Blimp prompted the young Peter Ustinov to cast him in his remarkable first West End play The Banbury Nose. Incarcerated in a mental home by Army authorities as "psychologically unsuitable to write Army film scripts" (having just co-written The Way Ahead, the most successful example of the genre in history... Ustinov was forbidden to attend the first night; but Roger at once persuaded a stagestruck Brigadier to revoke the order, and ensure that Ustinov enjoyed his moment of success. Ustinov asked him to become godfather to his daughter Tamara, and later starred him in his ebullient film of Anstey's schoolboy classic Vice Versa.

Wartime also involved some hardy tours with ENSA, taking theatre to the troops; and on a trek to India, the young Bryan Forbes and another forlorn corporal found themselves abandoned at Cairo airport after rattling around a freezing, empty Stirling bomber with the Liveseys and various high-ranking officers - though all the men had democratically chipped in to pee into the frozen hydraulic system to get the undercarriage down. They were not part of the party, and everyone else had forgotten them - but within minutes Roger came back to rescue them, and treated the two NCOs to a slap-up dinner in a scandalised officers' mess.

In 1947 Roger and Ursula toured and starred in the West End for a year in Ever Since Paradise, the play specially written for them and directed by J B Priestley. This uniquely delightful, funny, thought-provoking entertainment was a special celebration of their personal qualities, as the films had been; and has never since been staged with other actors.

Then in 1950, while on tour in the States, Roger was struck down by cancer and almost died. At the crisis of his post-operative illness, Ursula leaned over him and said with all the love and strength in her power, "Roger, you will live." It turned the tide. But the damage to his body had badly shaken Roger's instinctive confidence and buoyancy, essential to him both as a person and as an actor. Ursula, desperate to help him face life after the colostomy, finally asked Babe Zacharias to help. (They were both most enthusiastic, though inexpert, golfers.) The famous player, who had had the operation herself, gladly agreed to come and talk to him, and Roger, greatly cheered, set about getting fit to act again, with Ursula's help. Most of the revenue from his major films had gone on American medical bills, however, and it would be an uphill struggle.

Something similar, though on a smaller scale, had happened to Jack. An injury to his leg during a two-day action sequence for a film had badly shaken his confidence. Though he disguised the problem from his colleagues, the accident was instrumental in his decision to move to the States and "start again" in Hollywood.

He was a respected character actor in Britain, remembered for films like The First Gentleman, but had never starred as Roger had done. Stopping off in New York en route for California, he accepted a theatre engagement to keep his hand in - and played the Father in The Entertainer for two years - a role Roger later played in Olivier's film. Finally getting to Hollywood, Jack was able to play cricket in earnest at last, succeeding his friend C Aubrey Smith as captain of the expatriate actors' team.

Convalescing at Plough Cottage, Roger's thoughts turned to his family's work in the Victorian travelling theatre, and with the enthusiastic help of his secretary, Biddy Neal, he beguiled the time with research. They decided to invite reminiscences in a letter to Mexborough's local paper - and a flood of letters poured in at once; an astonishing, delightful, touching collection, often ill-spelt, sometimes quixotic, but bursting with what the apparently lost work of the Liveseys had meant to dozens of people who had been to their theatre fifty, sixty years before. Biddy travelled to Mexborough, met many of them and struck up correspondence; and Roger, heartened, grew stronger, ready to work again.

He never completed his research into the family history - he was soon too busy working. The letters were packed away in an old suitcase, but their message had done its work. He and Ursula were touring in Australia when news came that his final medical check was clear; he got off the train for a quiet celebratory drink, missed its trans-continental departure and didn't manage to catch up with it for two days! They had a great Old Vic season to come - his Falstaff, and Captain Shotover; television, records, films like The League of Gentlemen, Tom Jones, The Entertainer. But never again the films which used his personal quality as Michael Powell's had done. "He was," said Powell, "a figure of romance. Arthurian romance."

The Liveseys' last West End play together was An Ideal Husband, and when they left the cast after a year Roger insisted on doing the traditional stage fall for such an occasion, despite everyone else's concern about the colostomy bag and the risk of hurting himself.

It was a cast of old friends, or no one would have known; It was generally assumed that his illness had been connected with his husky voice - in fact the effect of an early operation on his nose - and record books perpetuate the mistake. It might have prejudiced the flow of work if the state of his health had been general knowledge.

It was a tragedy that, having cared for him so devotedly for years, Ursula herself developed cancer and died first. Roger nursed her alone and in secret for eighteen months, not telling even the family what was wrong. At last her condition was too serious for them to manage any longer at Plough Cottage, and she had to go to hospital for the last weeks of her life. Roger, distraught and heartbroken, could not bear to return to the cottage, but did not close it up; he lent it to a young local couple who had nowhere to live, while he moved into a house in the nearest village, where they had once set up a store and post office to help the local community.

Only surviving Ursula for little more than a year, Roger was grateful to be partly occupied with his last television series, The Pallisers, in which he played the Duke of St Bungay. It was a happy note that one of the stars was Susan Hampshire, whom he and Ursula had met when she was six, appearing with Ursula in The Woman in the Hall. Enchanted with her, and grieved to have no children of their own, they had wanted to adopt her, and always remained in touch, commissioning jewellery from her when she took classes in the work at school, writing and sending presents. Now they were acting together in his last show.

There was a sudden resurgence of Roger's cancer at Christmas, and he died a few weeks later, early in 1976. At his funeral Eileen and Peggy, startled by an outlandish roaring sound in the chapel, discovered it was made by the mechanism of an iron lung. A boy in the next village, who had had to live in one for years, had been regularly visited by Roger through all that time - he had insisted on being carried to pay Roger his respects.

Kenneth More wrote to The Times of Roger and Ursula's encouragement and friendly invitations when he was an unknown and lonely ex-Service beginner. "I cannot possibly describe what it meant to be so recognised," he said; in days when other stars simply did not mix with new actors.

There are no more Liveseys in the theatre, and it might appear that all their effort, their great hearts, all the magic and courage of their work, "like an insubstantial pageant faded" have "left not a wrack behind".

Not so. Their gift to everyone whose life touched theirs was the theatre's true gift - the gift of love; and it can never die.

Back to index