In 1947, Jack Cardiff won the Oscar for best colour

cinematography for Black Narcissus. He said at the time,

"When ever I gaze at it, I always seem to grow a few

inches" I asked him if at the age of 83, does he

still gets that feeling?

Oh yes, I still have a great

affection for it, some people think the Oscars are a lot

of nonsense, but it isn't a lot of nonsense, it's an

accolade, which if you've done something well is a very

honourable thing, I like the idea. A while ago, I was in

Hollywood and went out three weekends running with a

Hollywood cameraman to lunch or to the beach, and each

time he brought along one of his three ex-wives. On the

last occasion, we were all about to get into his car

which was in the garage, when a cupboard opened and an

Oscar rolled out, and he shoved it back in with his foot.

I thought "Oh my goodness, to do that sort of thing

to an Oscar."

The Oscar sits on a shelf with several other

glittering prizes on a large shelf in a kitchen come

sitting room at Jack and Nicki Cardiff's house in rural

Essex. I struggled hard to resist the urge to ask if I

could pick it up, and hope maybe some its glory would rub

off, but I resisted the temptation to ask, and now regret

my self control.

So many autobiographies are available where there is

little or no real substance to write about; Jack really

has been there, read the book and met the cast and then

made the movie. Martin Scorsese, has written the foreward

to "Magic Hour." This is Jack's autobiography

and is shortly to be published in paperback. Scorseese

sums up the spirit of the book - "It is a wonderful

opportunity to survey the career and artistic evolution

of this man whose name had become synonymous with

Technicolor, from his itinerant beginnings on the

vaudeville circuit with his parents to his apprenticeship

in the silent cinema, from his work as an operator on

films like Hitchcock's "The Skin Game" and

"The Man Who Could Work Miracles" to his acing

of a Technicolor exam with his knowledge of painting,

from his adventurous days shooting travelogues and war

footage with the mighty Technicolor camera, in battle

ships in wartime seas, on top of erupting volcanoes, in

burning deserts and steaming jungles - to his magnificent

work as a cinematographer and his experiences as a

director."

It is probably for this magnificent work as a

cinematographer that Jack is best known, He won the

Academy award for "Black Narcissus", and was

nominated for "War and Peace",

"Fanny" and "Sons and Lovers" (the

latter as director) and should have been at least

nominated for the "African Queen", "The

Red Shoes" and "A Matter of Life and

Death."

As the son of a theatrical mother and father, Jack's

first experience with the Movies was in front of the

camera as a child in 1918. With the decline in music hall

style entertainment, it was quite fortuitous that the

family were around the burgeoning film industry. Jack

received a rudimentary education, because of his parents

travels, and at an early age on leaving school, found

himself in a film studio as his first job as a junior

whose job it was to fetch Vichy water for a flatulent

director - It's an ill wind....

The film was the 1928 version of the 'Silent

Informer.' During the making the assistant cameraman

called the young Jack over, "When I tell you, during

the shot, I want you to rotate the lens from this pencil

mark to the other one." The scene was shot and Jack

asked what he had done, "Well sonny, you followed

focus." And that was the start of it all.

Jack followed the traditional route through the

craft, and he admitted to me recently, that the only

reason he wanted to join the camera department was that

they got to travel to some exotic locations. "The

only problem was it was several years before I got the

chance, although I did get to the Isle of Wight for half

a day." One night the B&D Studios caught fire.

Jack and his colleagues Ted Moore and Skeets Kelly

managed to get to the camera room and rescue some of the

cameras.

The next morning we felt we would be called heroes

for rescuing these cameras, the management didn't like us

at all, the cameras were all insured and they said that

they wished that we hadn't done what we did, because they

would have got a lot of money from the insurance. One

camera wasn't insured; it was a Debrie, a brand new

French camera, and the Debrie company were so delighted

that they gave Ted Moore 15, and they gave me a three

day holiday in Paris.

For some one who's early education could best be

described as itinerant, it is not so strange that his

thirst for knowledge and culture was stirred by reading a

pornographic book. He then galloped through every great

book he could lay his hands on, and an appreciation of

art followed. He was interviewed at Denham for the chance

to go to America and learn about the new Technicolor

process. After the usual grilling, Jack informed the

panel that he was a mathematical dunce, and that he was

the wrong candidate. One of the panel then asked what he

thought made him a good cameraman, he replied that it was

from observing light; the light in houses, trains and

buses at various times of day and the light that the Old

Masters used in their paintings. He then went on to back

it up extolling the techniques of Rembrant, Vermeer,

Pieter de Hooch and Georges de la Tour. Jack went on the

course.

In 1936 Jack was to meet Count von Keller who wanted

to hire a Technicolor camera and cameraman so that they

could travel the world and make professional travelogues.

This gave Jack the chance to do all the travelling he

wanted, travelling light or more exactly travelling

without lights (only two reflectors), across the

civilised world and considerably beyond.

I asked Jack if it were possible to spot a cameraman

by his lighting style in the same way that it is possible

to identify a painter. I don't know, I have been told by

some people that they can. I really can't see it myself,

I get pre-occupied with watching the performances. I

remember filming a long scene in 'Black Narcissus' with

Deborah Carr, I was so absorbed with the marvellous

performance, that after the take Micky (Michael Powell)

came over and said "I suppose you'll want to do

another take." I looked at Micky and said

"Why?" "Didn't you see the lamp go out at

the back?" he said. "No, Michael, I didn't see

it, no-one is going to notice that, the performance is

wonderful" and Michael said "Great, print

it."

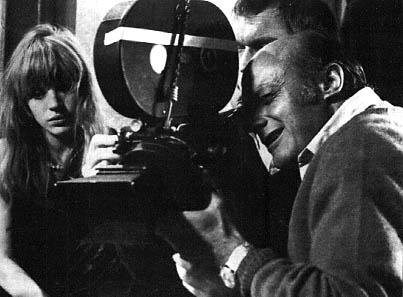

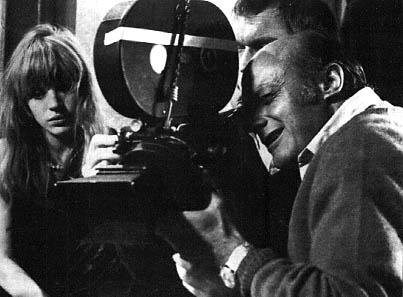

The working relationship with the director Michael

Powell developed through "A Matter of Life and

Death" and "Black Narcissus." Powell had

encouraged Jack to experiment and make suggestions. Jack

being the enfant terrible of Technicolor suggested on a

dawn sequence, the use a slight fog filter - unheard of

in those days. The only problem was this was the last

day's shooting with Deborah Carr. The laboratory called

the next morning, and said the rushes were no good.

I felt sick, Technicolor said everything was ruined,

Deborah would have to be paid a fortune to work another

day on overtime. Then we had a viewing, and as the stuff

came on the screen I knew it was good, Michael said,

"I love it, its just what I wanted." The

Technicolor boys were there saying, "Don't you think

in a drive in people will think it's out of focus?"

Michael gave them a strict lecture on what was art and

what was not art.

It was during the last days of filming "Black

Narcissus," Michael Powell said to me "What do

you think of ballet?" I was stupid enough to say

"Not much, it's so precious - all those sissies

prancing about." Micky showed more amusement than

outrage, "Have you ever been to a ballet?" I

admitted that I hadn't been since I was a child,

"Well you've a lot of catching up to do, our next

production is all about ballet. It's called "The Red

Shoes" and I want you to soak up ballet as if your

life depended on it. You'll be given tickets to go to

Covent Garden - practically every night." I didn't

realise how lucky I was at the time. I thought it was

going to be a boring chore. In a very short time I was

well and truly hooked.

I asked Jack if he considered "The Red

Shoes" to be one his best films, I think so, first

of all there was a great atmosphere on the film, Michael

Powell had this power of installing enthusiasm in people.

At the beginning of the picture he made a long speech

saying "this is going to be the best film you've

ever worked on and we're going to have a lot of fun with

it." and we did, we had a wonderful time in the

South of France.

Nothing was too risky for Michael, He was the most

stimulating director I ever worked with. I always knew if

I tried something daring, he'd back me up as he had done

over the fog filter on "Black Narcissus." I had

a gadget made to change the camera speed during a scene.

This was used to great effect when a dancer leapt into

the air, and just before the apex of flight, by speeding

up the camera, I was able to slow the action so they

would appear to hover in the air. I changed the speed

with pirouettes so that a dancer would start off at

normal speed and then as I changed the camera speed to

only four frames a second, she would whirl faster and

faster until she was a spinning blur.

We had to have a spotlight for the ballet sequence.

as the speed of Technicolor was slow in those days, this

spotlight had to be really powerful. We ended up with a

specially constructed water-cooled arc lamp of 300 amps.

It was a wonderful piercing ray of glory like a shaft

from heaven. Also after a conversation with Peter Mole

from Mole Richardson, I was able to use two prototype 225

amp lamps which he called "Brutes". The first

ever made.

"I'm probably best known for "The Red

Shoes", I'm often introduced as the man who shot

"The Red Shoes", but I was never nominated for

an Academy Award for it. After I won the award for Black

Narcissus, the Society of American cameramen (who put

forward the nominations) were concerned that it would put

them in a bad light if a non-American were to win the

award two years running, and so they prevented this

happening by not nominating me in the first place."

From the work with the Archer Company, Jack moved on

to "Scott of the Antarctic" "The

laboratory deserved an Oscar for matching the colour of

the studio footage with those of the exteriors." -

to "Under Capricorn" with a now established

Hitchcock who pursued the method of choreographing

continuous takes, and moving the camera almost all the

time within a 'trick' set, which was a progression from

'The Rope'. "This involved meticulous pre-production

planning, and by the time it came to shooting it,

Hitchcock seemed rather bored with the whole project.

In 1950, a joint British-American production was

started. "It will be so simple," said the

director. "We'll make the whole film on a raft.

We'll put a replica of the boat on it using the boat as a

stage, and we can be towed along the rivers of Africa

while we shoot to our hearts content." Jack Cardiff

had been taken on board "The African Queen" by

its director John Huston. Almost all of the was film shot

in Africa with almost all of the problems. The first

location was in the heart of Tsetse fly country, the

second was in what they had all imagined to be the quiet

tranquillity of Lake Albert, where we boarded the

houseboat the Lugard II, which was to be our

accommodation. We were all so ill, my operator Ted Moore

and I worked a bizarre version of musical chairs, when my

temperature reached 104, I would lie down and Ted would

take over; in turn, I would do his job until he

recuperated. There were only two people who didn't go

down with the sickness and that should have provided the

clue, because they were Huston and Bogey. They never

drank water, Only neat, germ proof whisky. It was later

discovered that the special filters through which the

drinking water was pumped, were missing and we had all

been drinking unfiltered water with every microbe in the

book of tropical disease.

As a cinematographer, Jack has earned a reputation as

a wizard of Technicolor, he also has one for his ability

to capture on film some of the world's most beautiful

women. Ava Gardner, Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida,

Ingrid Bergman and Marilyn Monroe. It is not just a

matter of capturing their beauty with flattering angles

and careful lighting, but giving them the confidence to

believe they look good on camera, enabling them to give

their best performance. Jack was hired to photograph

"The Prince and the Showgirl" and had to go and

meet Marilyn Monroe and her husband Arthur Miller, who

were staying at Parkside House at Englefield Green. He

met Arthur first, who said that Marilyn had just woken

up, and she would be out in a minute. Then she appeared,

sped swiftly to Miller's arms, then she slanted a shy

sleepy smile at me. She didn't say anything at all - not

even 'hello'. Then gazing at me with cosy triumph, she

murmured softly to Miller, "Isn't he wonderful,

darling? He's the greatest, and I've got him." I

gave them a silly smile, feeling uncomfortably gift

wrapped. I later left the house quite convinced I had met

an angel.

The film that followed was not to be an easy passage,

the mixture of Marilyn Monroe and Lawrence Olivier who

wore the hats of both star and director. Olivier was

exasperated by the behaviour and performance of his

female lead, who was arriving later and later, and

needing more and more takes, and which he felt was

worsened by the presence of Paula Strasberg, Marilyn's

Drama coach. Jack was caught in the cross-fire and whilst

he could see Olivier's point, he could also see the

torment that was going on behind Monroe's eyes." She

just froze when she had to go out and face being stared

at by hundreds of pairs of eyes." Jack remained

friends with Marilyn up until her premature death, a

subject on which Jack has strong opinions.

Errol Flynn was in the later part of his career in

1953 and was working with Jack Cardiff on the

"Master of Ballantrae". Some time later, Flynn

encouraged Jack to go to Rome to photograph 'Crossed

Swords' - "Bring the family, you'll love Rome."

What followed was an fraught co-production which was not

helped by Flynn's drinking and drug habits. At the end of

this Flynn approached Jack with an offer to direct

"William Tell" with Flynn and his manager,

Barry Mahon, as producers. It was the offer Jack had been

waiting for.

Not content with the role of one of the worlds finest

cinematographers, Jack wanted to direct. His first

project was "William Tell." The whole project

was built on a fabrication. The film was backed by an

Italian, Count Fossataro, a man of good standing, or so

his bank had told Flynn and Mahon. The problem lay in

that in Italian banks 'to be of good standing' means that

he had more than a couple of Lire in his account. Sadly

this was to all he had in his account. The film soon hit

the rocks, a large number of which had been used to erect

a stone village at the foot of Mont Blanc. The project

was killed completely when the two Cinemascope cameras

were confiscated (William Tell was to have been the

second film shot on Cinemascope - 'The Robe' being

first). 25 screen-time minutes of the film were shot, now

only 5 remain.

Jack went back to photographing films but waited for

his chance to chance to direct again. It came with a 'B'

picture 'Intent to Kill' a suspense film based in a

Montreal Hospital. Then in 1960, he was offered 'Sons and

Lovers' by Robert Goldstein. He had to lie to get it

saying that he had adored the book, which he had never

read. Jack assembled a superb cast, and crew and film a

large part of the movie in the places and amongst the

communities where Lawrence had actually lived.

I asked Jack if he found it difficult to let go the

reins and allow Freddie Francis light and photograph it

in his way. I made it clear from the outset that I did

not want to interfere. I had enough to do with the actors

and all the problems with Goldstein the executive who

never came to the studio. We were two days behind

schedule because it had been drawn up for the summer and

we actually shot it in the winter. Goldstein started

cutting scenes, so I called the cast together and told

them what was happening, I said that if I walked off the

picture, I would be replaced tomorrow, but if they were

to threaten to leave something would happen. It did, all

the scenes were put back.

The censors had been making strange suggestions from

the start. they wanted to replace Miriam's line "You

shall have me." with "I do love you."

After the shooting was finished, there was a battle with

the censors, over Clara's line "Is it me you want or

just it." Jack carried on regardless, ignoring all

the spurious requests and finished the film remaining

true to the Lawrence's book. This was only his third film

as director and he was nominated for an Academy Award for

it.

Jack often found himself directing difficult films

with demanding stars, he walked out on "The Long

Ships" three times. Not because of the explosive

nature of so many in this profession, on the contrary

because of others ranting and being difficult. I asked

Jack after having worked with some monsters in his time

what he was liked to work with. He describes himself as,

"One of the quiet ones as opposed to the the

shouting and screaming type, I was more in Carol Reed's

league," with a twinkle in his eye, and with typical

modesty Jack adds, "Only he was a better

director."

The British film industry went into something of a

decline, and it became difficult to get directing

assignments so for the next decade Jack moved among films

as either a director or a cinematographer or as in the

case of 'Girl on a Motorcycle' he did both. He got

nominated as best cinematographer for

"Fanny"(1960). It is at this point in the book

one can sense Jack's frustration, and possibly the only

real criticism is that this period from the mid sixties

to mid eighties are largely glossed over largely because

Jack was working as a cinematographer when he really

wanted to be directing. it would be interesting to

compare the on screen fire-power of 'First Blood II' with

the off screen battles of 'The Prince and the Showgirl'.

A very minor criticism of what is one of the best written

accounts of a life in the film industry.

Learning the cameraman's craft today, we usually find

we are walking a well trodden path, with so many of the

'rules' or guide-lines are laid down by those, like Jack,

who have passed this way before, occasionally when we try

something a little different, we usually find someone

else beat us to it. Sometimes it is almost impossible to

imagine what the industry was like, when the medium was

being discovered, through experimentation and more

importantly through original ideas. Jack was really one

of the pioneers of the craft not as a technician but as

an artist using the tools at the cutting edge of

technology. That is not to say that Jack is not

unimpressed with the work that is produced today, and he

told me. "The Bill has some of the best camera

operation I have ever seen."

At 83 most people would consider themselves well and

truly retired, not Jack, 'Magic Hour' is due to be

published in paperback, he is thinking about publishing a

book of photographs, working on some paintings to have an

exhibition and he is currently trying to put a small

project together, "to make a film about

England." I for one, am looking forward to seeing

it.

Magic Hour is published by Faber and Faber the

paperback release is due in August 1997