Submitted by

Christoph Michel

Miklós Rózsa

From: Double Life: The Autobiography of Miklós Rózsa, Composer

in the Golden Years of Hollywood.

Tunbridge Wells: The Baton Press. 1982. p.77-87.

(Ppbk. 1984, ISBN 0 85936 141 1)

Korda was responsible for the teaming of the English director Michael Powell

with the Hungarian writer-producer Emeric Pressburger, a partnership which

was to bear fruit in some of the finest British films of the forties and

fifties (e.g. The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus). The Spy

in Black was their first collaborative effort, and I did the music for

it. Some years later in Hollywood I got a telegram from Powell asking me

to join him in Canada to research Canadian folkmusic and then to return

to London to do the music for 49th Parallel. I had to refuse since

at that time I was committed to Korda and he wouldn't let me go; in the

event I was glad I did, since that film marked the cinematographic debut

of the composer who at that time was the undisputed leader of music in England,

Ralph Vaughan Williams.

London Films and Denham Studios had been financed by the Prudential Life

Assurance Company, and apparently, though Korda had made a great many films

between 1935 and 1938, the income wasn't quite as much as the Prudential

had hoped. So it was decided that the company should take over the running

of the studios and rent out the space, while Korda formed his own private

company, Alexander Korda Films. All Korda's employees were moved to what

was known as 'the old house', a lovely building at one end of the studios

beside a gently flowing river, and the big studio, the old London Films

Studio, was now no longer under the control of Alexander Korda.

In a way this was all to the good, because Korda always did his best work

when he was concentrating on a single project, and not when ten separate

films were being made at the same time, all demanding his constant attention.

He was a member of the American company, United Artists, which had been

set up to finance and distribute the films of Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks

Senior, Mary Pickford, Samuel Goldwyn, David O. Selznick and Korda. This

meant that his films were assured of immediate release in America and were

shown all over the world.

After the great box-office success of The Four Feathers, Korda's

biggest since Henry VIII and The Ghost Goes West, Alex asked

me to come and see him. He told me how pleased he was with the music and

announced that the next picture I was to work on was very important from

a musical point of view. This was The Thief of Bagdad.

He told me the story, which was an Arabian Nights fantasy, and said that

my contract would run from that day and that he was increasing my salary

by a large amount. I must admit that my salary had been rather low up until

then. The last thing I would have done would have been to ask for a rise,

but now Korda was giving me one without my having to ask.

The film was already in preparation. I read the script and thought it not

very good; and apparently that was the general opinion. Directors came and

went. Korda tried several for a couple of weeks each but couldn't decide

on the right one. Eventually he announced that he had settled for a German

by the name of Dr Ludwig Berger. Berger had recently made Les Trois Valses

in Paris with music by Oscar Straus, the famous Austrian composer of

operettas such as The Chocolate Soldier. Berger arrived at Denham

to start work on The Thief of Bagdad, and shortly afterwards Korda

summoned me to his office for a private meeting. He had a serious problem:

Dr Berger wanted Straus to write the score for The Thief of Bagdad.

Not only had Korda promised the job to me and had me under contract to do

it, but he did actually want me, and not Straus, to compose the score. But

everything was ready for the production to start: sets were constructed,

actors were hired. A number of musical sequences were necessary before shooting

began and Berger was insisting on Straus. Korda had to start production

in order to keep the support of his financial backers, for he needed their

money to pay his employees' wages. He was obliged, for the moment, to go

along with Berger and engage Straus, but he wanted me to trust him to see

me right in the end. Naturally this came as a shock, but I told Korda that

I trusted him completely and would do whatever he wanted. He had already

talked the matter over with Berger and it was understood that while all

the pre-production music would be provided by Straus, all the dramatic and

colouristic music would be written by me. In any event, I was still on the

production team. I agreed - I had no choice.

|

|

Muir Mathieson

|

|

|

Dr Ludwig Berger

|

Slowly the music began to arrive from Vichy, where Straus was taking a cure.

It was impossible - typical turn-of-the-century Viennese candy-floss. I

stuck to my promise to Korda and didn't say a word, but Muir Mathieson was

outspoken in his denunciation and went round telling everyone, including

Vincent Korda, that these songs would ruin not only the picture, but the

company as well.

The next day Mathieson and I had a cryptic summons from Alexander Korda's

office to report to him at ten the following morning. When we arrived his

secretary looked very cowed and said, 'He's in a vile temper this morning.

I don't envy you having to see him.' Dr Berger arrived and was shown straight

into Korda's office. A few minutes later Korda called us in with an imperious

'Boys!' It was always a bad sign when he addressed you as 'boy', and he

sat there behind his desk glowering ferociously at us like a Thundering

Jove, a Jupiter Tonans. 'Boys', he said again, 'I understand you have been

making disparaging remarks about Mr Straus's songs. Is this true?' Mathieson

immediately lost his temper and let fly at Korda. 'It certainly is,' he

shouted. 'His music stinks to high heaven and it is my duty as your musical

director....' Korda heard him out and then said, 'Right. I want it clearly

understood by the pair of you that in all artistic matters the sole and

final arbiter is Dr Berger. It that quite clear? That's all.' Mathieson

stormed out in a rage and Dr Berger went away grinning like a Cheshire cat.

Just as I was about to leave, Korda called me back, and asked me my opinion

of Straus's music. I told him that frankly the music would be quite charming

for a Viennese revue of 1900, but that it was completely unsuitable for

an oriental fantasy. He then told me to go ahead and write the music as

I thought it should be written, and to report back to him when it was done.

Meanwhile I wasn't to tell a soul what I was up to, not even Mathieson.

A week later I rang him up to tell him I had finished and did he want to

hear what I'd done? 'No,' he said. 'What I'm going to do is give you an

office next to Dr Berger's. Keep playing your music until he comes in and

listens to it. Don't say I told you to do it, just say you wrote it off

your own bat and let him hear it.' So I moved into the office next to Dr

Berger's and from ten in the morning until five every evening I thumped

out my music as loudly as I possibly could. The secretaries in the offices

above and below me complained that it was impossible for them to get any

work done with all the noise, but I just kept on playing. The first day

nothing happened. The second day I could hear Berger's voice through the

wall, so I played more loudly than ever, but still he didn't come in. On

the third day, he stormed into my room and said, 'I've been listening to

this now for two whole days. Do you mind telling me what's going on?' I

was all wide-eyed innocence. 'Well, you see, Dr Berger,' I began, 'I had

a few ideas for the picture and I wrote them down I thought you might be

interested to hear them.' He said, 'We've already got all the music we want

and we won't even know what we need from you until after we've finished

filming. So what are you up to now? Mind you, there was one melody I rather

liked. You can play me that if you want.' So I told him I had written the

music for the 'Silvermaid's Dance'. He advised me that Straus had already

done that. I said I knew he had, but I had one or two ideas of my own, and

I played them to him. He didn't say a word. I played Sabu's song, then another

piece I had written. He paced up and down the room and left the room telling

me not to go and that he would be back shortly.

About ten minutes later he was back. 'I've been to see Mr Korda,' he said.

'I told him that I much prefer what you've done to what Straus has sent

us, but how am I going to tell the old man?' Now Korda had a genius for

this kind of manipulative diplomacy. He was like a brilliant chess player,

moving his pieces round the board, always half-a-dozen moves ahead of his

opponents. It was incredible how he had manoeuvred Berger into this position,

and it made me very pleased that I had put my trust in him.

A telegram was sent to Oscar Straus who alleged that his reputation was

being ruined and threatened to sue, but Korda paid him his full fee and

I was formally reinstated as the sole composer on The Thief of Bagdad

.

The day after Berger had changed his mind about Straus, Korda called me

into his office, looked at me, smiled and said, 'It worked.' I thanked him

for the confidence he had shown in me and he said, 'My boy, I know your

music. I had every reason to be confident.' He told me the Iyrics were to

be written by his friend Sir Robert Vansittart, chief diplomatic adviser

to the British Foreign Office. I didn't know that Sir Robert was a Iyricist,

but Korda said, 'He is a fine poet, a good writer, and I think you will

like him.' I did. He was, without doubt, the finest human being I have ever

met in my life.

I knew very little about his role in British politics. First of all, I understood

nothing about politics; secondly, all I did know was what I read in the

newspapers, and Vansittart wasn't somebody who appeared in the limelight

very often. He was the Grey Eminence, the power behind the throne at the

Foreign Office. As far as I was concerned, he was my collaborator and Iyric

writer. He was over six foot, lean, active, with a strong profile, a born

diplomat. He would have been about fifty years old at this time. He never

treated me as a 'bloody foreigner'. We were equal partners: he wrote the

words and I wrote the music.

There were several jobs to be done. Sir Robert was working on the script

with Miles Malleson, who as well as being a fine actor - he was playing

the part of the Sultan—was also a writer. The three of us discussed

the songs which would have to be written. For the opening in Basra harbour

we needed a song about the sea; we also needed one for the Genie, who was

to be played by the popular Negro actor, Rex Ingram, already well-known

in Hollywood and on the New York stage. And, of course, Sabu had to have

his song.

During the whole summer of 1939 I spent every weekend at the beautiful,

sixteenth-century Denham Place, Sir Robert's home. Throughout 1938 there

had been grave fears that war was imminent, and I stood in Piccadilly Circus

with thousands of others watching the illuminated headlines on the night

that Chamberlain came back from Berchtesgaden with the promise of 'peace

in our time'. There was great rejoicing. Few people would have admitted

that it was only a temporary reprieve and that war, sooner or later, was

inevitable. Sir Robert had played a key role throughout this difficult time.

On my last visit to Paris I had completed my Three Hungarian Sketches

and played the work to Charles Münch, who was enchanted with it

and thought it better than my Variations. He was going to conduct it with

the Lamoureux Orchestra. I asked his permission to dedicate the piece to

him and he granted it. On my return to London I wrote and told him of the

problems I was having with The Thief of Bagdad - this was before I had

become the one and only composer working on the film. He sent me a postcard

in reply: 'You have your problems with The Thief of Bagdad. We have ours

with The Thief of Berchtesgaden.'

|

|

Sir Robert (later Lord) Vansittart

|

He also told me that he had invited Karl Straube and his Thomanerchor to

Paris to perform Bach's B minor Mass and that Straube had expressed a wish

to see me again. I went over to Paris for the performance and afterwards

at the reception I renewed my friendship with Straube. He had suddenly grown

older and his hair was snow-white. He was sixty-five and he seemed terribly

tired after the performance. He congratulated me on my success; he thought

it a pity that Breitkopf & Härtel hadn't published my Variations

, but he knew why they hadn't. It was typical of his generous nature,

particularly as he had himself been responsible for my early contact with

Breitkopf to say that it didn't matter who published the piece; the important

thing was that it was a huge success.

It was a strange, rather disturbing gathering. Frau Straube expressed strong

Nazi sympathies. She kept referring to 'these little Austrians,' and said,

'They all thought they were going to get the best positions in their country

when we took over. That's ridiculous. We put our own people in the best

positions.' Straube himself said nothing. The boys in the choir were all

new to me, of course. They all looked strikingly blond and Teutonic and

in their stiff behaviour there was something reminiscent of the Hitler Youth.

Münch made a speech in his Alsatian German, saying that music was the

only truly international medium, that it brought people together and created

strong emotional bonds across radical differences of language and culture.

'We are French,' he said, 'and you are German. We are happy to have you

here among us and I hope our friendship, rooted in music, will grow and

flourish for many years to come.' Poor Charles Münch. How could he

know that less than a year later these same boys would be back in Paris

in uniforms with machine guns in their hands?

Eulenburg wrote to tell me that my Three Hungarian Sketches had been

accepted for the International Music Festival in Baden-Baden. This was a

major piece of luck for me, because all the top conductors and critics in

Europe would be attending. A little later the conductor of the Baden-Baden

Festival wrote to say that seven rehearsals were scheduled and he was inviting

me to attend them as well as the festival itself, all my expenses to be

met by the German government. He also sent me the full programme for the

festival, which looked very interesting. Every nation was represented, and

my piece was the official Hungarian entry. The BBC Chorus was giving a complete

evening concert of new English choral music.

The papers were full of the worsening political situation. Austria had already

been annexed; Czechoslovakia was gone, and Poland, with its vulnerable Danzig

Corridor, was under constant threat. The newspapers were beginning to advise

British subjects not to travel in Germany. Although I wasn't a British subject

I felt I owed allegiance to Britain. I rang the BBC and asked if the BBC

Chorus were still intending to go to Baden-Baden and was told that the trip

had definitely been cancelled. I told the gentleman at the BBC what my own

position was, and he advised me not to go. I decided not to. I wrote to

the conductor and told him I was very busy - which was true—and couldn't

afford to take a whole week to come to the festival. After the performance

he sent me a telegram to say that the work was a great success and the reviews

were outstanding.

I was warned by Eulenburg that I would be committing artistic suicide and

ruining him as well if I persisted in dedicating the Sketches to

Charles Münch. In his experience, no conductor would be interested

in a piece dedicated to another, especially an up-and-coming conductor like

Münch. But I had already asked Münch's permission for the dedication

and he had given it, so Eulenburg proposed printing only six copies with

the dedication in place, two for Münch and four for me. I hope dear

Münch never found out.

Shortly afterwards I received another letter from the publishing firm, but

this time it wasn't signed by Eulenburg but by Schulze, his business manager.

He told me that Eulenburg had been sent to a concentration camp and asked

me for help on his behalf. Unfortunately, of course, there was nothing anyone

in London could do. Then, just before war was declared, I received a letter

from Eulenburg himself, from Switzerland, informing me that he and his family

were now safely together in Basle.

So the storm clouds were gathering in 1939, but I was so busy and excited

about The Thief of Bagdad, now with a script that had been improved

beyond all recognition, that I was almost unaware of what was going on in

the world around me. Naturally enough, not everything was plain sailing

- it never is when a film is being made.

|

At work on The Thief of Bagdad

(with Toscanini's tacit disapproval)

|

Berger wanted me to do the market scene in the manner of a musical; that

is, he wanted the music first, to which he would then shoot the action.

The scene introduced Sabu as a thief in the market place: everybody was

bustling around selling while Sabu was busy stealing. We worked out the

scene in terms of action and choreography and ended with a sequence over

five minutes long. After I had written the music Berger went over it with

me and I made many adjustments, slipping in an extra two bars here, re-introducing

Sabu's theme there. Finally we were all satisfied and we recorded it. Then

came the playbacks, and Berger wanted the actors to move in strict synchronisation

with the music. Naturally enough the result was chaos. Little Sabu was expected

to move like a puppet in a puppet theatre, the actors like dancers in a

pantomime, but to appear at the same time to be acting quite spontaneously

and naturally. They just couldn't get it right, and after a week's work

we had practically nothing to show. When Korda saw the result he all but

burst into tears, it was so awful. He called me in and asked me if I could

adjust the same music to the scene after the sequence had been shot;

I told him of course that was perfectly possible, whereupon he put a stop

to any further antics of this kind.

|

On the set of The Thief of Bagdad

with June Duprez

|

In the end the only sequences shot to pre-composed music were those involving

special effects - the gallop of the Flying Horse and the Silvermaid's Dance.

The scene with the Flying Horse, in which the Sultan is so enchanted by

the magic toys and the ride across the sky above Bagdad that he gives his

beloved daughter's hand to Jafar the Magician, was a collaboration between

Vansittart, Miles Malleson and myself. The script and the music were conceived

as a single entity; the three of us spent all day at the piano at Denham

Place working out the details.

Vansittart and I never established a fixed pattern of working together.

Sometimes the music came first, sometimes the Iyric. In the case of the

'Lullaby of the Princess' he wrote the poem first, which I then set to music

and which in fact became the main love theme of the picture. With 'Sabu's

Song', again an important song because it had to reappear throughout the

film, the tune came first and the words followed later.

|

|

Letter from Vansittart

|

I soon became almost a permanent fixture in Vansittart's home. He spent

the week at his flat in London, but every weekend we were together at Denham

Place, and I soon got to know his enchanting wife. We never discussed politics,

but these were critical days for Britain. Stafford Cripps was in Moscow

trying to forge an alliance with the Russians, but was pipped at the post

by Ribbentrop. The Russian-German agreement came as a great shock to England,

but whether Vansittart was expecting it or not I am unable to say. Sometimes

we would be working at the piano and the butler would come in to call him

to the telephone. When he came back he never revealed whether it had been

good or bad news (though sometimes he looked ashen-faced) and I never asked

him. We would simply carry on from where we had left off.

|

The Figaro article

about Vansittart

|

Somehow the foreign press got wind of the fact that he was writing the lyrics

for The Thief of Bagdad. It was at about this time that Figaro

in Paris printed an article to the effect that if the chief diplomatic

adviser to the British Foreign Office had time to write Iyrics for a motion

picture with me, there could be no immediate danger of war. A fortnight

later, on 3rd September 1939, war was declared. Thereafter my relationship

with Vansittart changed. He opened up and talked about subjects I wouldn't

have dared mention to him. He told me fascinating things about the people

he met in diplomatic circles, and about the past few years when he had constantly

and unavailingly been trying to warn the British government of what was

happening on the continent. He talked about the 1936 Olympics at which he

and his wife had met Hitler. He spoke fluent, idiomatic French, and also

German and Arabic, just as a senior British diplomat should. Even in 1936

he had been thought of as a Germanophobe and a warmonger. Hitler had been

told that he was a swarthy little Jew and was shocked to be introduced to

the tall, imposing British gentleman who spoke perfect German.

Vansittart presented me with two volumes of his poetry, suggesting I might

find something in them to set to music. One collection, The Singing Caravan

, he had written at the time he was British Ambassador in Teheran. I

set two of them for contralto and piano, 'Beasts of Burden' and 'Un Jardin

dans la Nuit'. I found the latter title too close to Debussy's 'Jardins

sous la Pluie', and asked him if I could change it. It became 'Invocation',

published later in America and re-published now in England.

There was panic in London at the outbreak of war because people were caught

unprepared. On that Sunday, soon after Chamberlain had come on the radio

to announce that 'a state of war exists between Germany and England', I

was driving towards London when there was an air raid warning. It was a

false alarm, but of course all the traffic was stopped and we had to get

out and lie down in a ditch. Petrol rationing was introduced and I moved

to a little cottage in Chalfont St. Peter only ten minutes away from the

studios to make things easier. The Korda brothers set up home together in

Denham village.

Slowly The Thief of Bagdad progressed towards completion. Two additional

directors, Michael Powell and Tim Whelan, were put to work on it, but still

sequences were missing and the picture took shape in a very haphazard manner,

not as originally envisaged. Not until February 1940 did we get to the final

recording sessions.

|

|

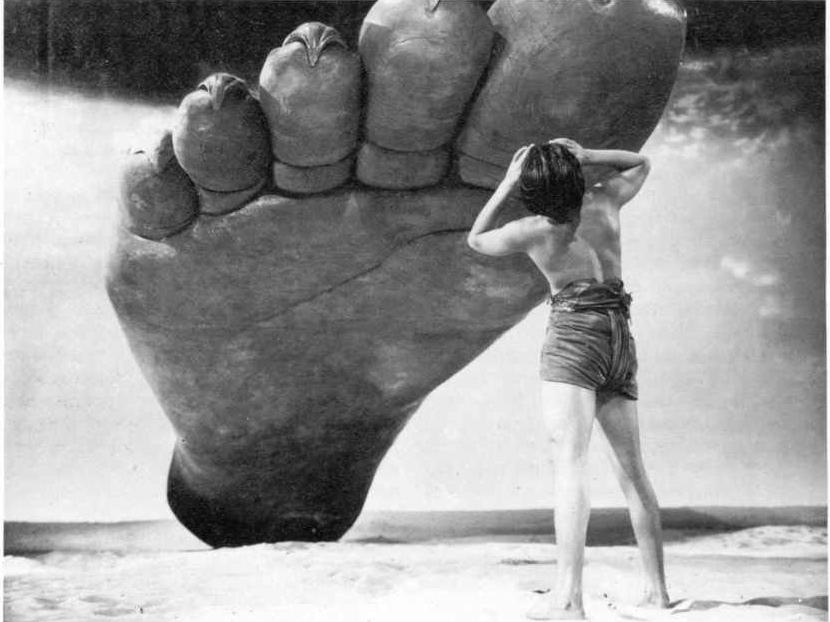

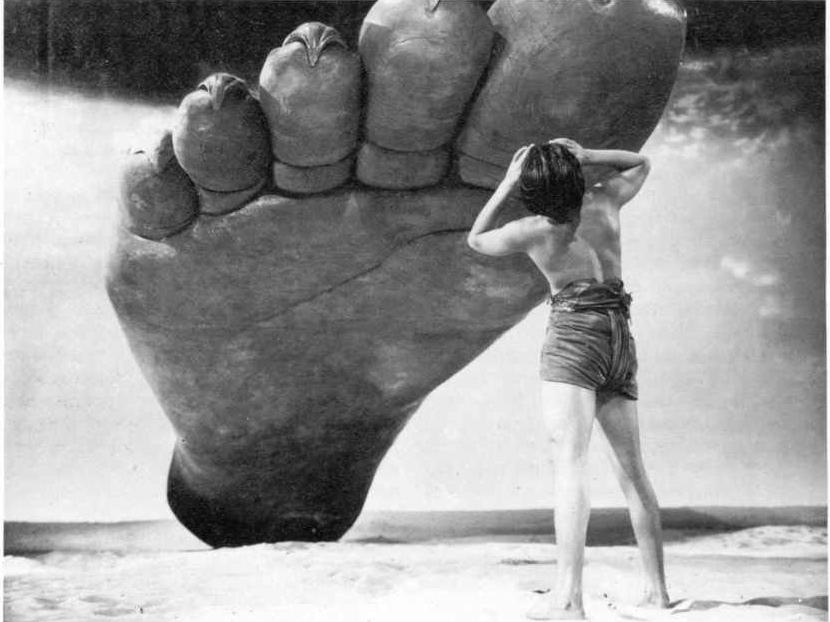

Sabu menaced by the Djinn (Rex Ingram)

|

I had met Maurice Martenot in Paris and I had once written a Berceuse

for the electronic instrument he had invented, the Ondes Martenot.

I decided it would be the right instrument to use for the Djinn. It would

be an unworldly tone-colour for an unworldly happening, the Djinn escaping

from his bottle and later flying through the Grand Canyon with Sabu on his

shoulders. We wrote to Maurice Martenot asking him to bring his instrument

to England and he agreed, but by the time of the recording he had been

called up and was somewhere defending his country. So I had to forget about

the Ondes Martenot for the next five years.

Eventually Berger returned to Holland leaving Bill Hornbeck to cut the picture

together as best he could. Alexander Korda left for the States. My work

on the film seemed to be complete, but one day I heard from David Cunnyngham

that arrangements were being made to shoot the missing scenes in America

and that United Artists were putting up the money. Everyone who was directly

involved in the production would be needed in Hollywood to finish the film.

I had never even dreamed of going to America. My Variations had been

well received when performed in Chicago, but America was a long way off

and it took five or six days to get there, so you had to have a good reason

for going. Well, I had to go now. I had fought so hard to write the music

for The Thief of Bagdad, and if I didn't go to America now it would

be finished by someone else, which was the last thing I wanted. David Cunnyngham

explained the various ways I could make the journey. American and English

passenger ships were no longer crossing the Atlantic directly, but I could

get an American ship from Genoa, though that route too was likely to be

closed shortly. I could take the train from Paris to Genoa, but getting

from London to Paris was going to be the difficult part. There were two

possibilities. I could either make the dangerous sea crossing, or I could

fly. I had never been up in a plane, and I was a poor sailor. Cunnyngham

said drily, 'You stand a good chance of being shot down over the Channel,

which at least has the virtue of being a quick death. Or you could be sunk,

which would be considerably less pleasant. It's up to you.' Sometimes I

find the British sense of humour a little hard to take. I told Cunnyngham

I had never flown in my life before and asked if he had. He looked at me

from behind his glasses and said casually, 'Oh yes'. When I told this story

to a friend later he burst out laughing. It turned out that Cunnyngham had

been an ace RAF pilot in the First World War and that his answer to me had

been a typical piece of British understatement.

I was sad to be leaving London. I had been happy there, I liked the English

and I had felt at home. I had been able to write both my own music and music

for films in the way I wanted to, always bearing in mind the kind of contribution

Honegger had made to the cinema. I was sorry too to be saying goodbye to

my beloved Trinity College and to the Civil Service Orchestra, who were

still meeting every week to play good music badly but with great enthusiasm.

My plane left from Croydon, and I expected the journey to Paris to last

about an hour and a half. After five hours or so, while we were still in

the air, I began to wonder whether it would have been better to take the

risk of being sunk by a submarine. Then suddenly I saw the Eiffel Tower.

I learned that we had had to take a roundabout route via the Channel Islands

to avoid German planes. The sight of Paris was incredible. We had had ten

months of blackout in London; the foggy, unlit streets were a constant danger

for the pedestrian, for even car headlights were masked. But Paris was lit

up like a Christmas tree, another world altogether. Nobody seemed worried

- they trusted their Maginot Line. I saw all my friends, said goodbye to

them and caught the train for Genoa where I found my ship in the harbour.

The trip took ten long days. We were to call at Gibraltar on the way. I

spotted a familiar face: it was Noel Coward. He usually sat reading in a

deckchair. I was sure everybody must have recognised him, but he talked

to no one, and no one bothered him. When we dropped anchor at Gibraltar

a cutter came alongside and took him off. We waited about ten hours, then

the boat brought him back and we set sail again. Later I read that he had

been sent to America by the authorities for propaganda purposes, and I assumed

that his short visit to Gibraltar was to meet the Governor or to receive

a final briefing.

Charles Boyer's mother was also on board, a lovely, elegant, elderly lady.

When at last we arrived in New York, there were Charles Boyer and his wife

to meet his mother, and Gertrude Lawrence waiting for Noel Coward. They

embraced and seemed overjoyed to see each other again.

After a few days at the St. Regis Hotel in New York (Korda's favourite),

I set off for Hollywood. I went there, as I thought, for a month or so,

forty days at the most. Now, forty years later, I am still there.

Rózsa, Miklós: Double Life: The Autobiography of Miklós

Rózsa, Composer in the Golden Years of Hollywood.

Tunbridge Wells: The Baton Press. 1982. pp.77-87.

(Paperback edition 1984, ISBN 0 85936 141 1)

Back to index